Tutorials & Guides

TPE: Emblem, Wabi-Sabi

The Expanded Image. Hypermedia students composed an image of wide scope in four steps, extended over a semester: 1) Family Memory, read John Briggs, Fire in the Crucible, on the wide image; 2) Entertainment narrative, read Zinsser, Worlds of Childhood; 3) Community History, read Momaday, Rainy Mountain; 4) Emblem, read Leonard Koren, Wabi-Sabi: for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers. Japanese enjoys a rich vocabulary of aesthetic terms, with Wabi-Sabi one of the most important. Introducing this book to students (which they invariably liked), I asserted that it was the best single book on the poetics of “image” that I had ever read. There were certain books I introduced with some fanfare, using hyperbole as a substitute for experience, to overcome the insecurity of thinking that while Koren’s book was good, there must be other books that were better somewhere else. University of Florida is rated as a “good bargain,” since it has one of the lowest tuitions of any AAU school: $6500 a year. My introduction claimed that this book was as true at UF for $6500 as it was true at Stanford for $45,000. Helen Cixous’s Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, I continued, is true for $6500. At Stanford for $45,000 there is no fourth step. Similarly Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millennium, still lacks the sixth memo (the lecture series one short at Calvino’s death) at Stanford, as it is at UF. The motivation for the hyperbole and performative framing was part of introducing students to theopraxesis, the three capabilities received from Avatar, that Koren made explicit in his exposition of Japanese traditional culture and aesthetics.

–How an Image becomes Wide. Koren demonstrates how a detail of the world is selected as a vehicle for a poetic image: for example, a worn shingle on an old hut, with a streak of rust descending from an iron nail. The tenor (theme) of this vehicle is coded in Japanese traditional culture, relative to the wisdom metaphysics of Buddhism, to express an existential insight into time and entropy known as wabi-sabi. “Wabi-Sabi can be called a ‘comprehensive’ aesthetic system. Its world view, or universe, is self-referential. It provides an integrated approach to the ultimate nature of existence (metaphysics), sacred knowledge (spirituality), emotional well-being (state of mind), behavior (morality), and the look and feel of things (materiality)” (Koren, 41). The instruction was not to seek Wabi-Sabi in one’s own experience, but the equivalent, the mood and atmosphere, to find one’s personal version of what was modeled in Japanese tradition. The folk traditions of Blues into Jazz in global Creole syncretism (mufarse into tango, saudade into samba) is central to the thymotic and erotic dimension of world materialized in digital electracy. Koren’s analysis demonstrates how to expand the two-part vehicle and tenor of image into a six-part inventory. Students generated their emblems productive of wide image by answer six questions posed by Koren: three for vehicle; three for tenor. The three questions addressing tenor (themata) are the same three articulated in the catechism of modernism, directing theopraxesis. One implication, to be developed further, is that the system of capabilities is not confined to the Western Tradition, but functions globally across cultures and civilizations.

–How an Image becomes Wide. Koren demonstrates how a detail of the world is selected as a vehicle for a poetic image: for example, a worn shingle on an old hut, with a streak of rust descending from an iron nail. The tenor (theme) of this vehicle is coded in Japanese traditional culture, relative to the wisdom metaphysics of Buddhism, to express an existential insight into time and entropy known as wabi-sabi. “Wabi-Sabi can be called a ‘comprehensive’ aesthetic system. Its world view, or universe, is self-referential. It provides an integrated approach to the ultimate nature of existence (metaphysics), sacred knowledge (spirituality), emotional well-being (state of mind), behavior (morality), and the look and feel of things (materiality)” (Koren, 41). The instruction was not to seek Wabi-Sabi in one’s own experience, but the equivalent, the mood and atmosphere, to find one’s personal version of what was modeled in Japanese tradition. The folk traditions of Blues into Jazz in global Creole syncretism (mufarse into tango, saudade into samba) is central to the thymotic and erotic dimension of world materialized in digital electracy. Koren’s analysis demonstrates how to expand the two-part vehicle and tenor of image into a six-part inventory. Students generated their emblems productive of wide image by answer six questions posed by Koren: three for vehicle; three for tenor. The three questions addressing tenor (themata) are the same three articulated in the catechism of modernism, directing theopraxesis. One implication, to be developed further, is that the system of capabilities is not confined to the Western Tradition, but functions globally across cultures and civilizations.

–Poetics: Image expanded into Emblem. The expanded image consists of two registers: material; metaphysical. Working with the narratives generated in composition of mystory, students must commit to one pedagogical object (magic tool), some detail found in at least one of the diegesis of the popcycle, to serve as logo or brand icon for the wide image. In Ulmer’s case (Noon Star), the repeating detail (like the dogs repeating in Momaday’s section III) was a five-pointed star: Family memory (the red star on his sheet music of the march, Garry Owen; Entertainment mythology (the film High Noon, Gary Cooper as Will Kane, discarding his sheriff’s star in the dirt after the gun fight); Community history (“General” Custer’s badge of rank, and Indian name, Son of the Morning Star). The three material questions are: 1) what is the prop/ icon? Ulmer chose the tin star sheriff’s badge to represent this materiality. 2) What are its attributes? (what mood or atmosphere is expressed that distinguishes this icon from its archetype, configuring it specifically for me. The context of High Noon star thrown in the dirt expresses rejection and disgust with the hypocritical authority symbolized in the badge. 3) Archetype: what is the conventional meaning associated with this icon in the archive? (the five-pointed star has an extensive presence throughout many cultures).

–Poetics: Image expanded into Emblem. The expanded image consists of two registers: material; metaphysical. Working with the narratives generated in composition of mystory, students must commit to one pedagogical object (magic tool), some detail found in at least one of the diegesis of the popcycle, to serve as logo or brand icon for the wide image. In Ulmer’s case (Noon Star), the repeating detail (like the dogs repeating in Momaday’s section III) was a five-pointed star: Family memory (the red star on his sheet music of the march, Garry Owen; Entertainment mythology (the film High Noon, Gary Cooper as Will Kane, discarding his sheriff’s star in the dirt after the gun fight); Community history (“General” Custer’s badge of rank, and Indian name, Son of the Morning Star). The three material questions are: 1) what is the prop/ icon? Ulmer chose the tin star sheriff’s badge to represent this materiality. 2) What are its attributes? (what mood or atmosphere is expressed that distinguishes this icon from its archetype, configuring it specifically for me. The context of High Noon star thrown in the dirt expresses rejection and disgust with the hypocritical authority symbolized in the badge. 3) Archetype: what is the conventional meaning associated with this icon in the archive? (the five-pointed star has an extensive presence throughout many cultures).

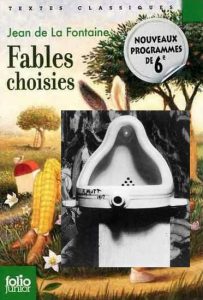

–Fable: What resources are available for inquiry and expression in the conditions after Nietzsche, the history of an error, after the simultaneous withdrawal of the true world and the apparent world along with it? The time is noon (the shortest shadow). What remains is fable, Nietzsche said. What are the possibilities of fable as genre? Duchamp improvised one approach, perhaps not even yet fully appreciated. His Readymades are fables, albeit weak (faible) fables, in that they provide the illustrations only (the emblems, impresas). He intimated his variation on the mode with his most notorious instance, whose title “Fountain” translates “La Fontaine,” antonomasia between common and proper noun, evoking the name of the author of many fables in the common “fountain,” itself a euphemistic title for a urinal. Ulmer’s collage of the urinal with a cover of La Fontaine’s book make the joke explicit. Duchamp’s commitment to the punning bachelor machine logic central to modernism is well known. He acknowledged his attendance at a performance of a stage adaptation of Raymond Roussel’s 1910 novel Impressions of Africa as a turning point in his career (Roussel’s method of composition used generative puns). It has been suggested that some of the Readymades at least are comments on dreams described in Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, hence that they use rebus methods (visualizations evoking words). Freud noted, for example, that many dreams are triggered when sleepers experience the need to urinate (the dream allows sleep to continue briefly). The text of the fabled fountain is provided by its history, being as it is the most influential (if not the “best”) art work of the twentieth century, including its status as a prank, and all the manipulations Duchamp performed to put the image of La Fontaine into circulation, recorded in Thierry De Duve’s Kant After Duchamp. What is the moral of the readymade fable?

–Fable: What resources are available for inquiry and expression in the conditions after Nietzsche, the history of an error, after the simultaneous withdrawal of the true world and the apparent world along with it? The time is noon (the shortest shadow). What remains is fable, Nietzsche said. What are the possibilities of fable as genre? Duchamp improvised one approach, perhaps not even yet fully appreciated. His Readymades are fables, albeit weak (faible) fables, in that they provide the illustrations only (the emblems, impresas). He intimated his variation on the mode with his most notorious instance, whose title “Fountain” translates “La Fontaine,” antonomasia between common and proper noun, evoking the name of the author of many fables in the common “fountain,” itself a euphemistic title for a urinal. Ulmer’s collage of the urinal with a cover of La Fontaine’s book make the joke explicit. Duchamp’s commitment to the punning bachelor machine logic central to modernism is well known. He acknowledged his attendance at a performance of a stage adaptation of Raymond Roussel’s 1910 novel Impressions of Africa as a turning point in his career (Roussel’s method of composition used generative puns). It has been suggested that some of the Readymades at least are comments on dreams described in Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, hence that they use rebus methods (visualizations evoking words). Freud noted, for example, that many dreams are triggered when sleepers experience the need to urinate (the dream allows sleep to continue briefly). The text of the fabled fountain is provided by its history, being as it is the most influential (if not the “best”) art work of the twentieth century, including its status as a prank, and all the manipulations Duchamp performed to put the image of La Fontaine into circulation, recorded in Thierry De Duve’s Kant After Duchamp. What is the moral of the readymade fable? –Martin Kippenberger, “Rameau’s Nephew,” 1988

–Martin Kippenberger, “Rameau’s Nephew,” 1988 This pictorial tradition can be traced back to an engraving by Marc Antonio. It shows an almost naked woman of Giorgionesque type watering a flower. This enigmatic motif can be explained with the help of the literary tradition. It is a symbol of “Grammatica.” As the plant grows through watering so the young mind is formed through the study of grammar. In late antiquity grammar became the foundation of the liberal arts.

This pictorial tradition can be traced back to an engraving by Marc Antonio. It shows an almost naked woman of Giorgionesque type watering a flower. This enigmatic motif can be explained with the help of the literary tradition. It is a symbol of “Grammatica.” As the plant grows through watering so the young mind is formed through the study of grammar. In late antiquity grammar became the foundation of the liberal arts.

Catechism: Wide Image. The catechism of modernism (drawing on the Western Tradition) is articulated in Kant’s philosophy and Gauguin’s painting. The answers to the questions are specific to each person, and are generated during the composition of the wide image. Several posts are required to unfold this poetics, by means of which egents learn to actualize in their own projects the intelligence potential (latent) in the cultural archive. This archive in its global version functions for electracy the way Avatar functioned for orality: source of absolute knowledge (the project of Avatar Emergency was learning to receive this communication of Avatar). One of the first things that happens in transition from one apparatus to another is the mise en machine of the previous apparatus. As McLuhan observed, the content of the new medium is the old medium (literacy put oral mythologies into writing; electracy digitized the libraries). The remainder of the apparatus epoch is devoted to invention and diffusion throughout society of the new metaphysics (operating practices).

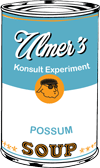

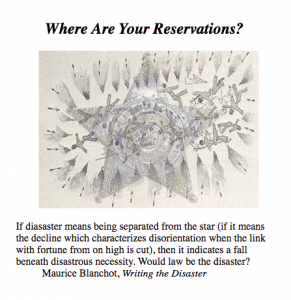

Catechism: Wide Image. The catechism of modernism (drawing on the Western Tradition) is articulated in Kant’s philosophy and Gauguin’s painting. The answers to the questions are specific to each person, and are generated during the composition of the wide image. Several posts are required to unfold this poetics, by means of which egents learn to actualize in their own projects the intelligence potential (latent) in the cultural archive. This archive in its global version functions for electracy the way Avatar functioned for orality: source of absolute knowledge (the project of Avatar Emergency was learning to receive this communication of Avatar). One of the first things that happens in transition from one apparatus to another is the mise en machine of the previous apparatus. As McLuhan observed, the content of the new medium is the old medium (literacy put oral mythologies into writing; electracy digitized the libraries). The remainder of the apparatus epoch is devoted to invention and diffusion throughout society of the new metaphysics (operating practices). –Emblem. The translation of mystory into wide image is mediated by emblematics. The emblem (having the same structure as a generic advertisement), considering its historical relationship with allegory, expresses in condensed form the image of wide scope ( sinthome, Lacan) that emerges in the making of a mystory (it embodies the pattern of signifiers that repeat when the makers situation is mapped across the popcycle). Studio and Textshop exercises explore the form, including its history from its introduction in the Renaissance through to contemporary advertising. An advantage of the form is just this combination of archival presence and pop familiarity. Ulmer designed this emblem based on his mystory: Motto is “pithy,” aphoristic, allusive, to produce an evocative connotation when combined with the picture. The epigraph is informational, clarifying what is suggested in the motto-picture juxtaposition.

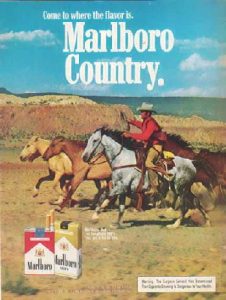

–Emblem. The translation of mystory into wide image is mediated by emblematics. The emblem (having the same structure as a generic advertisement), considering its historical relationship with allegory, expresses in condensed form the image of wide scope ( sinthome, Lacan) that emerges in the making of a mystory (it embodies the pattern of signifiers that repeat when the makers situation is mapped across the popcycle). Studio and Textshop exercises explore the form, including its history from its introduction in the Renaissance through to contemporary advertising. An advantage of the form is just this combination of archival presence and pop familiarity. Ulmer designed this emblem based on his mystory: Motto is “pithy,” aphoristic, allusive, to produce an evocative connotation when combined with the picture. The epigraph is informational, clarifying what is suggested in the motto-picture juxtaposition. –Advertisement.The Marlboro Cowboy

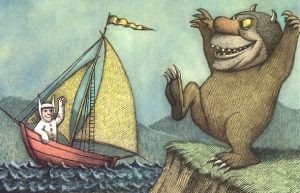

–Advertisement.The Marlboro Cowboy Maurice Sendak is best known for his Caldecott Medal winning illustrated children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963), made into

Maurice Sendak is best known for his Caldecott Medal winning illustrated children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963), made into  –Family (Personal): Composition of mystory usually begins with a memory from early childhood, life with the family. Up to three such memories are allowed, to avoid getting stuck deciding on one that is most important (that dilemma if it arises is resolved when the remaining slots are filled, following the rule what resembles assembles). Sendak proposed two memories: the first was one of his earliest, an encounter with one of the pedagogical objects Pasolini mentioned, a book his older sister received from her book club. The book was very thick with a hardcover of pale green with gold lettering. Although not yet able to read, Sendak was fascinated with the book and demanded to have it, creating so much commotion the parents made his sister give it to him. When he finally returned it to his sister it was in bad shape, including suffering from being licked all over.

–Family (Personal): Composition of mystory usually begins with a memory from early childhood, life with the family. Up to three such memories are allowed, to avoid getting stuck deciding on one that is most important (that dilemma if it arises is resolved when the remaining slots are filled, following the rule what resembles assembles). Sendak proposed two memories: the first was one of his earliest, an encounter with one of the pedagogical objects Pasolini mentioned, a book his older sister received from her book club. The book was very thick with a hardcover of pale green with gold lettering. Although not yet able to read, Sendak was fascinated with the book and demanded to have it, creating so much commotion the parents made his sister give it to him. When he finally returned it to his sister it was in bad shape, including suffering from being licked all over. I was eleven when I saw the movie, and I remember it vividly because of how intensely in frightened me. The moment I am talking about is the one when Dorothy is trapped by the Wicked Witch of the West, and the witch takes an hourglass and turns it over and says something horrible like, “When the sand runs out, you’re dead, honey.” Judy Garland is left alone in the room, and one of her best moments ever was her way of saying, “I’m frightened,” and then, as though that realization has just actually dawned on her, says it a second time, “I’m frightened.” I still remember how her hand went to her head–the way she had of fluttering her hand, her desperation was so convincing. There was no way out of that room, nothing she could do. And suddenly, in the witch’s crystal ball, she sees her Auntie Em, back in Kansas, standing in the yard and calling to her. And she rushes to the crystal ball, and stands over it and screams, “Auntie Em! Here I am!”

I was eleven when I saw the movie, and I remember it vividly because of how intensely in frightened me. The moment I am talking about is the one when Dorothy is trapped by the Wicked Witch of the West, and the witch takes an hourglass and turns it over and says something horrible like, “When the sand runs out, you’re dead, honey.” Judy Garland is left alone in the room, and one of her best moments ever was her way of saying, “I’m frightened,” and then, as though that realization has just actually dawned on her, says it a second time, “I’m frightened.” I still remember how her hand went to her head–the way she had of fluttering her hand, her desperation was so convincing. There was no way out of that room, nothing she could do. And suddenly, in the witch’s crystal ball, she sees her Auntie Em, back in Kansas, standing in the yard and calling to her. And she rushes to the crystal ball, and stands over it and screams, “Auntie Em! Here I am!” The major event of my childhood was the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932. That nightmare was probably the origin of my conviction that children can’t be shielded from frightening truths. Although I was only three, I remember intensely the details of the Lindbergh case. Lindbergh was our Prince Charles, and his wife was our Princess Di. I particularly remember a newspaper that had the front-page headline LINDBERGH BABY FOUND DEAD and a photograph of a scene in the woods with a black arrow pointing to something awful. I’ve since learned that Colonel Lindbergh threatened to sue if the New York Daily News didn’t have the morning edition pulled off the newsstands, so I guess not many people saw the picture. But I saw the picture.

The major event of my childhood was the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932. That nightmare was probably the origin of my conviction that children can’t be shielded from frightening truths. Although I was only three, I remember intensely the details of the Lindbergh case. Lindbergh was our Prince Charles, and his wife was our Princess Di. I particularly remember a newspaper that had the front-page headline LINDBERGH BABY FOUND DEAD and a photograph of a scene in the woods with a black arrow pointing to something awful. I’ve since learned that Colonel Lindbergh threatened to sue if the New York Daily News didn’t have the morning edition pulled off the newsstands, so I guess not many people saw the picture. But I saw the picture.

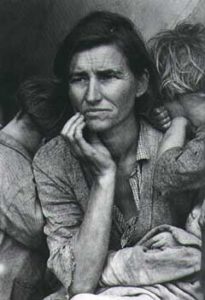

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times.

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times. This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”

This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”  Wonder Woman

Wonder Woman

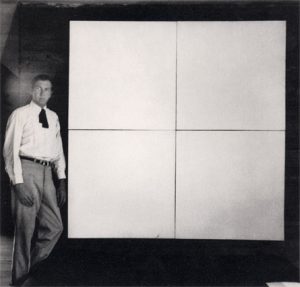

But not yet have we solved the incantation of this whiteness, and learned why it appeals with such power to the soul; and more strange and far more portentous–why, as we have seen, it is at once the most meaning symbol of spiritual things, nay, the very veil of the Christian’s Deity; and yet should be as it is, the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind.

But not yet have we solved the incantation of this whiteness, and learned why it appeals with such power to the soul; and more strange and far more portentous–why, as we have seen, it is at once the most meaning symbol of spiritual things, nay, the very veil of the Christian’s Deity; and yet should be as it is, the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind. Our first memories are visual ones. In memory life becomes a silent film. We all have in our minds an image which is the first, or one of the first, in our lives. That image is a sign, or to be exact, a linguistic sign. So if it is a linguistic sign it communicates or expresses something. I shall give you an example. The first image of my life is a white, transparent bind, which hangs–without moving, I believe–from a window which looks out on to a somewhat sad and dark lane. That blind terrifies me and fills me with anguish: not as something threatening and unpleasant but as something cosmic. In that blind the spirit of the middle-class house in Bologna where I was born is summed up and takes bodily form. Indeed the images which compete with the blind for chronological primacy are a room with an alcove (where my grandmother slept), heavy “proper” furniture, a carriage in the street which I wanted to climb into. These images are less painful than that of the blind, yet in them too there is concentrated that element of the cosmic which constitutes the petty bourgeois spirit of the world into which I was born. But if in the objects and things the images which have remained firmly in my memory (like those of an indelible dream) there is precipitated and concentrated the whole world of “memories,” which is recalled by those images in a single instant– if, that is to say, those object and those things are containers in which is stored a universe which I can extract and look at, then, at the same time, these objects and things are also something other than a container. . . . So their communication was essentially instructional. They taught me where I had been born, in what world I lived, and above all how to think about my birth and my life. Since it was a question of an unarticulated, fixed and incontrovertible pedagogic discourse, it could not be other–as we say today–than authoritarian and repressive. What that blind said to me and taught me did not admit (and does not admit) of rejoinders. No dialogue was possible or admissible with it, nor any act of self-education. That is why I believed that the whole world was the world which that blind taught me: that is to say, I thought that the whole world was “proper,” idealistic, sad and skeptical, a little vulgar–in short, petty bourgeois. (Pier Paolo Pasolini, Lutheran Letters, trans. Stuart Hood. Carcanet Press: New York, 1987).

Our first memories are visual ones. In memory life becomes a silent film. We all have in our minds an image which is the first, or one of the first, in our lives. That image is a sign, or to be exact, a linguistic sign. So if it is a linguistic sign it communicates or expresses something. I shall give you an example. The first image of my life is a white, transparent bind, which hangs–without moving, I believe–from a window which looks out on to a somewhat sad and dark lane. That blind terrifies me and fills me with anguish: not as something threatening and unpleasant but as something cosmic. In that blind the spirit of the middle-class house in Bologna where I was born is summed up and takes bodily form. Indeed the images which compete with the blind for chronological primacy are a room with an alcove (where my grandmother slept), heavy “proper” furniture, a carriage in the street which I wanted to climb into. These images are less painful than that of the blind, yet in them too there is concentrated that element of the cosmic which constitutes the petty bourgeois spirit of the world into which I was born. But if in the objects and things the images which have remained firmly in my memory (like those of an indelible dream) there is precipitated and concentrated the whole world of “memories,” which is recalled by those images in a single instant– if, that is to say, those object and those things are containers in which is stored a universe which I can extract and look at, then, at the same time, these objects and things are also something other than a container. . . . So their communication was essentially instructional. They taught me where I had been born, in what world I lived, and above all how to think about my birth and my life. Since it was a question of an unarticulated, fixed and incontrovertible pedagogic discourse, it could not be other–as we say today–than authoritarian and repressive. What that blind said to me and taught me did not admit (and does not admit) of rejoinders. No dialogue was possible or admissible with it, nor any act of self-education. That is why I believed that the whole world was the world which that blind taught me: that is to say, I thought that the whole world was “proper,” idealistic, sad and skeptical, a little vulgar–in short, petty bourgeois. (Pier Paolo Pasolini, Lutheran Letters, trans. Stuart Hood. Carcanet Press: New York, 1987).

When it comes to the image of wide scope (four or five fundamental images structuring imagination, and central to the history of invention), the prototype is Einstein’s compass (received from his father as a gift at age four or five): the wide image is a compass for the existential positioning system of learning, to orient egents tracking the vector of invention.

When it comes to the image of wide scope (four or five fundamental images structuring imagination, and central to the history of invention), the prototype is Einstein’s compass (received from his father as a gift at age four or five): the wide image is a compass for the existential positioning system of learning, to orient egents tracking the vector of invention.