MYSTORY: Maurice Sendak

Maurice Sendak is best known for his Caldecott Medal winning illustrated children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963), made into a film by Spike Jonze. Given the importance of childhood experience and how it is remembered to the Wide Image, Ulmer often included in the Hypermedia course a book of short essays by authors of children’s books on the art and craft of writing for children: Worlds of Childhood, edited by William Zinsser. (1998). Sendak’s essay, “Visitors from My Boyhood,” is organized as a mystory, addressing each of the popcycle slots in order to explain the source of his poetics, which suggests there is something intuitive or inherent in the popcycle as a matrix of imagination. Two other features recommending Sendak’s craft as relay for an Exercise is that his stories were rarely more than 300 words (the length of one micro fiction, the narrative building-block of mystory documentation), and the drawings did not merely illustrate the words but developed the diegesis of the world in their own terms. Students used Sendak’s essay as a relay: making an inventory of his popcycle; extracting a template of examples for each slot; finding equivalents in their own experience.

Maurice Sendak is best known for his Caldecott Medal winning illustrated children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963), made into a film by Spike Jonze. Given the importance of childhood experience and how it is remembered to the Wide Image, Ulmer often included in the Hypermedia course a book of short essays by authors of children’s books on the art and craft of writing for children: Worlds of Childhood, edited by William Zinsser. (1998). Sendak’s essay, “Visitors from My Boyhood,” is organized as a mystory, addressing each of the popcycle slots in order to explain the source of his poetics, which suggests there is something intuitive or inherent in the popcycle as a matrix of imagination. Two other features recommending Sendak’s craft as relay for an Exercise is that his stories were rarely more than 300 words (the length of one micro fiction, the narrative building-block of mystory documentation), and the drawings did not merely illustrate the words but developed the diegesis of the world in their own terms. Students used Sendak’s essay as a relay: making an inventory of his popcycle; extracting a template of examples for each slot; finding equivalents in their own experience.

–Family (Personal): Composition of mystory usually begins with a memory from early childhood, life with the family. Up to three such memories are allowed, to avoid getting stuck deciding on one that is most important (that dilemma if it arises is resolved when the remaining slots are filled, following the rule what resembles assembles). Sendak proposed two memories: the first was one of his earliest, an encounter with one of the pedagogical objects Pasolini mentioned, a book his older sister received from her book club. The book was very thick with a hardcover of pale green with gold lettering. Although not yet able to read, Sendak was fascinated with the book and demanded to have it, creating so much commotion the parents made his sister give it to him. When he finally returned it to his sister it was in bad shape, including suffering from being licked all over.

–Family (Personal): Composition of mystory usually begins with a memory from early childhood, life with the family. Up to three such memories are allowed, to avoid getting stuck deciding on one that is most important (that dilemma if it arises is resolved when the remaining slots are filled, following the rule what resembles assembles). Sendak proposed two memories: the first was one of his earliest, an encounter with one of the pedagogical objects Pasolini mentioned, a book his older sister received from her book club. The book was very thick with a hardcover of pale green with gold lettering. Although not yet able to read, Sendak was fascinated with the book and demanded to have it, creating so much commotion the parents made his sister give it to him. When he finally returned it to his sister it was in bad shape, including suffering from being licked all over.

–Entertainment (Mythology): The popcycle premise is that identity is configured through identifications with people, places, and things during formative years: just as one has a capacity (potentiality) for language in general, with one’s native language depending on the chance of birth; similarly one has a capacity for imagination, and one’s native imagination (wide image) is formed within uniquely particular circumstances (visceral learning). A shortcut to determine which identifications took is just introspection: what remains in memory? Writer’s are good relay resources modeling these shaping identifications of which they necessarily become aware in learning their craft. For Sendak the memory was of The Wizard of Oz, and one scene in particular that he said “stole into my life in 1939 and has been flooding my work continually ever since.”

I was eleven when I saw the movie, and I remember it vividly because of how intensely in frightened me. The moment I am talking about is the one when Dorothy is trapped by the Wicked Witch of the West, and the witch takes an hourglass and turns it over and says something horrible like, “When the sand runs out, you’re dead, honey.” Judy Garland is left alone in the room, and one of her best moments ever was her way of saying, “I’m frightened,” and then, as though that realization has just actually dawned on her, says it a second time, “I’m frightened.” I still remember how her hand went to her head–the way she had of fluttering her hand, her desperation was so convincing. There was no way out of that room, nothing she could do. And suddenly, in the witch’s crystal ball, she sees her Auntie Em, back in Kansas, standing in the yard and calling to her. And she rushes to the crystal ball, and stands over it and screams, “Auntie Em! Here I am!”

–Community (History). Family and Entertainment memories are personal and convincing because they “belong to me.” The assumption of the History slot in the popcycle is that identity is formed within a social habitus, which is a major source of education (interpellation) received uncritically and internalized. To access this level of distracted education students first must decide with which Community they identify. Not everyone grows up in a home town. Community could also be an ethnic group, religion, race, military branch, nation. Whichever Community chosen, the story told must be one the Community tells about itself (what the Community remembers). Many students actually knew very little about their communities, so that some research was required. A shortcut was just to recall street names, festivals, memorials, school names and the like, to make a short-list. At that point some personal connection may help the selection. Sendak’s relay is somewhat awry, in that he did have a strong emotional association with his History event (as did James Joyce with the history of Parnell). The particular contribution of the History story is register a Value important to the Community. The Event documented by Sendak was the story of the Lindbergh baby.

The major event of my childhood was the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932. That nightmare was probably the origin of my conviction that children can’t be shielded from frightening truths. Although I was only three, I remember intensely the details of the Lindbergh case. Lindbergh was our Prince Charles, and his wife was our Princess Di. I particularly remember a newspaper that had the front-page headline LINDBERGH BABY FOUND DEAD and a photograph of a scene in the woods with a black arrow pointing to something awful. I’ve since learned that Colonel Lindbergh threatened to sue if the New York Daily News didn’t have the morning edition pulled off the newsstands, so I guess not many people saw the picture. But I saw the picture.

The first phase of composition is to document each of these scenes (in your own popcycle): use micro fiction form, three micros (900 words) for each register, focusing on the diegesis of the event. The goal is to capture and annotate details of the scene, since wide images emerge in patterns of repeating signifiers.

Conduction (the fourth inference) is visceral. The image logic (reasoneon) we are developing as Gest suffers fallacies just as does the reasoning of abduction, deduction, and induction. Physiognomic inference operates in the type-casting of cinema, exploiting the same emblematics as racism, as in Nazi propaganda. This danger is a reminder that electrate rhetoric articulates the visceral dimension of intelligence (racists are physically repulsed by miscegenation, for example). This effect of concrete logic should not be denied or euphemized, but addressed as a resource in understanding the thymotic force operating in personal and public discourse.

Conduction (the fourth inference) is visceral. The image logic (reasoneon) we are developing as Gest suffers fallacies just as does the reasoning of abduction, deduction, and induction. Physiognomic inference operates in the type-casting of cinema, exploiting the same emblematics as racism, as in Nazi propaganda. This danger is a reminder that electrate rhetoric articulates the visceral dimension of intelligence (racists are physically repulsed by miscegenation, for example). This effect of concrete logic should not be denied or euphemized, but addressed as a resource in understanding the thymotic force operating in personal and public discourse. The existence of polysemous meaning has been noted throughout history–the repetition of patterns, the isotopies relating the different registers of the semiosphere (Lotman). Learning how to read these patterns is part of theopraxesis, since in the condition of the General Accident (that happens everywhere simultaneously [Virillio]) judgment and decision must be capable of registering macrocosm from details. That recognition of patterns does not dictate interpretation directly, to which may be added the Casandra effect. One of the better known examples of anticipation of disaster is the novel Futility, or The Wreck of the Titan, the 1898 novel by Morgan Robertson that foretold (in retrospect) the sinking of the Titanic (1912).

The existence of polysemous meaning has been noted throughout history–the repetition of patterns, the isotopies relating the different registers of the semiosphere (Lotman). Learning how to read these patterns is part of theopraxesis, since in the condition of the General Accident (that happens everywhere simultaneously [Virillio]) judgment and decision must be capable of registering macrocosm from details. That recognition of patterns does not dictate interpretation directly, to which may be added the Casandra effect. One of the better known examples of anticipation of disaster is the novel Futility, or The Wreck of the Titan, the 1898 novel by Morgan Robertson that foretold (in retrospect) the sinking of the Titanic (1912).

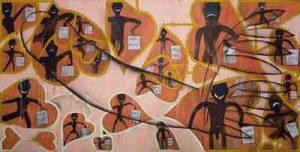

Many reports indicate that many millions of people will be displaced by these conditions globally. The present crisis is advanced warning of what is to come on a much larger scale. What policy response is in keeping with the imperative of well-being against disaster? The Zombie scenario warns of total war. Philosophers such as Jacques Derrida urge the self-described impossibility of Hospitality. It is important to note that left theory long ago identified our horror motifs as icons and emblems of life under Capitalism. Politics in any case concerns the just allocation of finite resources. The General Accident of climate change demands a holistic response.

Many reports indicate that many millions of people will be displaced by these conditions globally. The present crisis is advanced warning of what is to come on a much larger scale. What policy response is in keeping with the imperative of well-being against disaster? The Zombie scenario warns of total war. Philosophers such as Jacques Derrida urge the self-described impossibility of Hospitality. It is important to note that left theory long ago identified our horror motifs as icons and emblems of life under Capitalism. Politics in any case concerns the just allocation of finite resources. The General Accident of climate change demands a holistic response. Event Gest.

Event Gest.

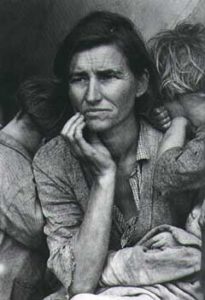

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times.

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times. This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”

This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”  Wonder Woman

Wonder Woman

Everyday life is a dimension of the lifeworld addressed in the tradition of Arts & Letters disciplines dating back to Marx’s commentaries on the revolutions in France (Paris) beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century. The issue is central to electracy, in that the digital apparatus is associated with the rise of the industrial city. The primary institutional condition to be remedied through a new (image) metaphysics is the impoverishment of everyday life codified in the concepts of alienation, reification, objectification. Marx diagnosed the problem as due to the division of labor, and the new cultural and social environment created by the commodity form in market capitalism under bourgeois hegemony. Life in the industrial city became “uncanny,” due to a discontinuity, disjunction, between individual agency and collective events. An equivalent of the Unconscious opened within culture, a return of the repressed in which citizens suffered the consequences of their collective actions as if visited upon them by divine powers (commodity fetishism). “Routine” in this context is the habituation of daily ritual that must be dispersed by means of shock arts devices of estrangement (defamiliarization).

Everyday life is a dimension of the lifeworld addressed in the tradition of Arts & Letters disciplines dating back to Marx’s commentaries on the revolutions in France (Paris) beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century. The issue is central to electracy, in that the digital apparatus is associated with the rise of the industrial city. The primary institutional condition to be remedied through a new (image) metaphysics is the impoverishment of everyday life codified in the concepts of alienation, reification, objectification. Marx diagnosed the problem as due to the division of labor, and the new cultural and social environment created by the commodity form in market capitalism under bourgeois hegemony. Life in the industrial city became “uncanny,” due to a discontinuity, disjunction, between individual agency and collective events. An equivalent of the Unconscious opened within culture, a return of the repressed in which citizens suffered the consequences of their collective actions as if visited upon them by divine powers (commodity fetishism). “Routine” in this context is the habituation of daily ritual that must be dispersed by means of shock arts devices of estrangement (defamiliarization).

Situation.What does it mean to approach Everyday Life with an aesthetic attitude? There is nothing novel about framing one’s quotidian roles in some state of mind — wisdom, science, religion. As practice, the aesthetic attitude is included within a situation, adding to the intentionality of some project the distance that generates aura of signification. “Situation” is a guideword, evoking the existentialist point that circumstances become a situation when considered from the point of view of one’s “project,” the goals of a practice, encountering a scene not indifferently but according to its affordances for some purpose. In a Visit (for konsult) this project or purpose is given an aesthetic frame.

Situation.What does it mean to approach Everyday Life with an aesthetic attitude? There is nothing novel about framing one’s quotidian roles in some state of mind — wisdom, science, religion. As practice, the aesthetic attitude is included within a situation, adding to the intentionality of some project the distance that generates aura of signification. “Situation” is a guideword, evoking the existentialist point that circumstances become a situation when considered from the point of view of one’s “project,” the goals of a practice, encountering a scene not indifferently but according to its affordances for some purpose. In a Visit (for konsult) this project or purpose is given an aesthetic frame. The function of heuretics is to create a discourse on method: The method you need has to be generated even while you are applying it. Blogs are a good support for this generative practice, since they enable a developmental unfolding. A project experiment is set (the design of konsult for EmerAgency catalysis of public policy dilemmas), a set of resources are chosen as generators, assigned to slots in the CATTt, and each resource is inventoried in turn, in a sequence from which emerges an intertext, to be synthesized and integrated into a working recipe. Blogs document this process, inventorying each resource as it is encountered, itemizing instructions from the operating features of the resource, testing them in part, while moving through the sequence, integrating instructions for further testing. The result is both a commentary on and demonstration of the desired poetics.

The function of heuretics is to create a discourse on method: The method you need has to be generated even while you are applying it. Blogs are a good support for this generative practice, since they enable a developmental unfolding. A project experiment is set (the design of konsult for EmerAgency catalysis of public policy dilemmas), a set of resources are chosen as generators, assigned to slots in the CATTt, and each resource is inventoried in turn, in a sequence from which emerges an intertext, to be synthesized and integrated into a working recipe. Blogs document this process, inventorying each resource as it is encountered, itemizing instructions from the operating features of the resource, testing them in part, while moving through the sequence, integrating instructions for further testing. The result is both a commentary on and demonstration of the desired poetics.

The further step of using the CATTt is to extrapolate from these operating features, to adopt them as forms only, substituting one’s own materials suggested by the relay, to test an allegory of prudence (aesthetic judgment) drawing on equivalents of the features found in the source Theory.

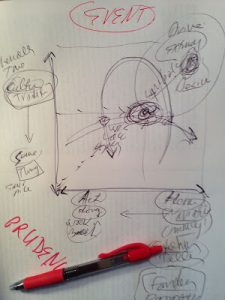

The further step of using the CATTt is to extrapolate from these operating features, to adopt them as forms only, substituting one’s own materials suggested by the relay, to test an allegory of prudence (aesthetic judgment) drawing on equivalents of the features found in the source Theory. This diagram sketch suggests a way to map the components of the exercise “Allegory of Prudence” onto some conventional dynamics of narrative semiotics:

This diagram sketch suggests a way to map the components of the exercise “Allegory of Prudence” onto some conventional dynamics of narrative semiotics:  These four codes provide four slots for the allegory: an action and an underlying narrative (fantasy); a feature of the scene (the prop or seme) and its associated mythology (aura). The fifth code is the Symbolic (alluding to Lacan’s Symbolic Order), which is the structuring or “anagogical” code of the social and civilizational context of the scene. This code is reprsented in the diagram by a partial version of one of Lacan’s schemas, showing the temporality of language, and of the unconscious (structured like a language). The Event alluded to in AE happens in this manner, constructing the time image of prudence. An initial satisfaction, experienced in infancy, remains latent and potentially present (flashes up at the moment of its recognizability, Benjamin says), triggered by some chance incident (Proust’s involuntary memory). The Symbolic code synthesizes the other four codes, addressing the paradigmatic axis of selection in terms of binary oppositions (male/female, death/life…), and the syntagmatic axis of combination in terms of primary exchanges in the life world– of language, wealth, and kinship. This circuit of remembrance through senation, this triggering of memory and imagination through the activation of somatic markers (Damasio, Neuroaesthetics), is the aesthetic homology to be correlated with mobile media in smart environments, to develop an electrate konsult.

These four codes provide four slots for the allegory: an action and an underlying narrative (fantasy); a feature of the scene (the prop or seme) and its associated mythology (aura). The fifth code is the Symbolic (alluding to Lacan’s Symbolic Order), which is the structuring or “anagogical” code of the social and civilizational context of the scene. This code is reprsented in the diagram by a partial version of one of Lacan’s schemas, showing the temporality of language, and of the unconscious (structured like a language). The Event alluded to in AE happens in this manner, constructing the time image of prudence. An initial satisfaction, experienced in infancy, remains latent and potentially present (flashes up at the moment of its recognizability, Benjamin says), triggered by some chance incident (Proust’s involuntary memory). The Symbolic code synthesizes the other four codes, addressing the paradigmatic axis of selection in terms of binary oppositions (male/female, death/life…), and the syntagmatic axis of combination in terms of primary exchanges in the life world– of language, wealth, and kinship. This circuit of remembrance through senation, this triggering of memory and imagination through the activation of somatic markers (Damasio, Neuroaesthetics), is the aesthetic homology to be correlated with mobile media in smart environments, to develop an electrate konsult.