SINTHOME/Theopraxesis

Jacques Lacan, The Sinthome, Seminar XXIII, 1975-76

Lacan offered seminars annually from 1952 to 1980. Lacan’s seminars make an important contribution to the Theory in the CATTt guiding the invention of Konsult in general, and theopraxesis in particular. In this later seminar Lacan makes explicit some connections with the sources of our project that until now operated as assumptions. The first of these relationships is outlined here.

Capabilities.

Real, imaginary, and symbolic strikes me as just as valid as the other triad from which, going by Aristotle, the juice was extracted to compose man, namely, will, intelligence, and affectivity. (Sinthome 126).

As discussed in the book, Konsult: Theopraxesis, one function of our experiment is to support a transition from literacy to electracy in education (to negotiate a passage from one apparatus to another). The pedagogy is centered on egents, the ones supposed to learn, appropriating the resources of Arts & Letters curriculum as means for students to undergo and develop their capabilities—their faculties, powers, virtues, potentiality—identified in the tradition dating from the invention of literacy in the Athenian academies as the embodied intellectual virtues: Theoria, Praxis, Poesis (theory, practice, poetics; thinking, doing, making; understanding, will, imagination). Kant’s Three Critiques take up this thread. The Third Critique promotes Aesthetics to equal status with Science and Morality, to propose aesthetic judgment as mediator bridging the abyss separating science and religion. Hannah Arendt took up Kant’s project as the best option for a Public Sphere in industrialized mass society after Auschwitz.

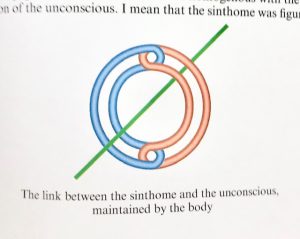

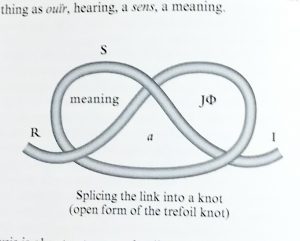

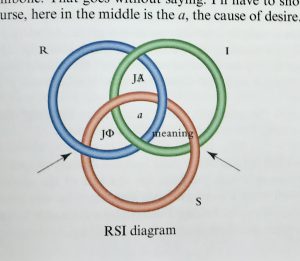

The importance of Lacan’s contribution is apparent in this context. His mnemonic image of the embodied virtues is a bag (the body, mathematically the empty set, the one) tied closed with cord (string, ficelles). RSI (playing on rhymes and puns with “heresy” and “airesis” or choice)—Lacan’s updating of the three faculties—Real, Symbolic, Imaginary—interrelate topologically, entangled in a way that Lacan explores through knot topology, with the Borromean knot specifically manifesting the sinthome (unique symptom). We have argued elsewhere that the sinthome helps account for the image of wide scope. One implication to be tested in our experiments is that in experience we encounter the apparatus stack (the popcycle) as entangled, knotted, in a manner articulated by topology. Lacan supplies one guide for the Kant-Arendt project, that we are calling theopraxesis: the virtues and their institutions already are fully integrated in a potential state (dunamis, but in a condition of privation, steresis). The “symptom” of this virtual condition is the polemos or seemingly irreducible conflict apparent in relations both macrocosmic and microcosmic of civilization.

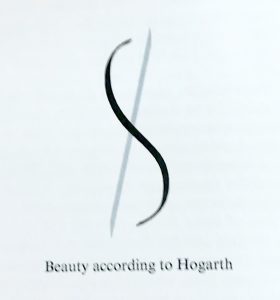

HOGARTH: Line of Beauty

A second affiliation with tradition important to note in this seminar is Lacan’s reference to Hogarth’s curved line of beauty as relevant to the genealogy of his knot topology. This connection makes explicit Lacan’s contribution to the larger question of the gramme, the invention of the plasmatic line in the Paleo apparatus, in continuing service up to the present, now augmented in electracy through animation and digital FX. Sergei Eisenstein cited Disney’s animated film, Steamboat Willie (1928) as a revelation of the new order opened up in media by the plasmatic line. We will have more to say about the ontological properties of this line.

A second affiliation with tradition important to note in this seminar is Lacan’s reference to Hogarth’s curved line of beauty as relevant to the genealogy of his knot topology. This connection makes explicit Lacan’s contribution to the larger question of the gramme, the invention of the plasmatic line in the Paleo apparatus, in continuing service up to the present, now augmented in electracy through animation and digital FX. Sergei Eisenstein cited Disney’s animated film, Steamboat Willie (1928) as a revelation of the new order opened up in media by the plasmatic line. We will have more to say about the ontological properties of this line.

–Scenario. Assuming familiarity with the synopsis of the narrative, we may outline the allegorical import. In general the narrative is instructive of mystorical design in that there is an isotopic rhyming between Dorothy’s world in Kansas and the fantasy world of Oz. The encounter of these two orders is dramatized when Dorothy’s house lands in Oz, crushing the Wicked Witch of the East, whose red shoes Dorothy inherits. The tornado that interrupted a family crisis in Kansas represents Disaster. Dorothy is egent, or soul (psyche) in the allegory, and her journey to find the Wizard to get his advice dramatizes the egent’s actualization of her capabilities in theopraxesis. The three capabilities (virtues, faculties) are represented by the three companions Dorothy meets along the way, the Yellow Brick Road. The three figures embody the significance of the lack articulated in the term “egent” (they lack). The three companions represent the three virtues in a state of privation, Steresis, potentiality not realized (im/potence). Their impotence is a projection of Dorothy’s virtuality, her lack, the condition of any ephebe on the way. The three figures manifest the tripartite system of virtues, but Baum euphemized the assignments somewhat, blending heart and gut. In our appropriation of the story for konsult allegory the alignment with the tradition is clear: Scarecrow wants a brain (Knowledge, Theoria, Head, Rulers); Lion wants courage, so heart (Will, Praxis, Guardians); Tin Woodman’s problem is not his “heart” but his “axe” (enchanted by the witch), which prevents him from loving (having sex). He represents Viscera (Desire, Poiesis, Workers).

–Scenario. Assuming familiarity with the synopsis of the narrative, we may outline the allegorical import. In general the narrative is instructive of mystorical design in that there is an isotopic rhyming between Dorothy’s world in Kansas and the fantasy world of Oz. The encounter of these two orders is dramatized when Dorothy’s house lands in Oz, crushing the Wicked Witch of the East, whose red shoes Dorothy inherits. The tornado that interrupted a family crisis in Kansas represents Disaster. Dorothy is egent, or soul (psyche) in the allegory, and her journey to find the Wizard to get his advice dramatizes the egent’s actualization of her capabilities in theopraxesis. The three capabilities (virtues, faculties) are represented by the three companions Dorothy meets along the way, the Yellow Brick Road. The three figures embody the significance of the lack articulated in the term “egent” (they lack). The three companions represent the three virtues in a state of privation, Steresis, potentiality not realized (im/potence). Their impotence is a projection of Dorothy’s virtuality, her lack, the condition of any ephebe on the way. The three figures manifest the tripartite system of virtues, but Baum euphemized the assignments somewhat, blending heart and gut. In our appropriation of the story for konsult allegory the alignment with the tradition is clear: Scarecrow wants a brain (Knowledge, Theoria, Head, Rulers); Lion wants courage, so heart (Will, Praxis, Guardians); Tin Woodman’s problem is not his “heart” but his “axe” (enchanted by the witch), which prevents him from loving (having sex). He represents Viscera (Desire, Poiesis, Workers). –Wizard. The scene of consultation with the Wizard, when Psyche and her three Capabilities make their requests, shows the full arrangement of apparati and their relationship at the collective level. In this expanded scene, the microcosm/macrocosm individual/collective isotopy is made explicit: Tin Man is Paleo (Family, sexual fertility), Lion is Oral (Church), Scarecrow is Literate (School), Wizard is Electrate (Entertainment). Much theory could be referenced here to support this configuration. To mention Lacan, for example, the Wizard is the Big Other, the one supposed to know, whose hold over us it is the purpose of therapy to dispel. The immediate value of the Oz allegory is to highlight this passage in education, the adventure of learning (dealing with the trials testing Psyche/Dorothy) as actualization of the three capabilities. Equally important is the fact that the Wizard is augmented capability, imagination mise-en-macbine, with the imperative of the allegory being for us to understand how Oz makes able, activates, the three virtues so Dorothy may return home (overcome disaster).

–Wizard. The scene of consultation with the Wizard, when Psyche and her three Capabilities make their requests, shows the full arrangement of apparati and their relationship at the collective level. In this expanded scene, the microcosm/macrocosm individual/collective isotopy is made explicit: Tin Man is Paleo (Family, sexual fertility), Lion is Oral (Church), Scarecrow is Literate (School), Wizard is Electrate (Entertainment). Much theory could be referenced here to support this configuration. To mention Lacan, for example, the Wizard is the Big Other, the one supposed to know, whose hold over us it is the purpose of therapy to dispel. The immediate value of the Oz allegory is to highlight this passage in education, the adventure of learning (dealing with the trials testing Psyche/Dorothy) as actualization of the three capabilities. Equally important is the fact that the Wizard is augmented capability, imagination mise-en-macbine, with the imperative of the allegory being for us to understand how Oz makes able, activates, the three virtues so Dorothy may return home (overcome disaster). –Tenor (Themata): Catechism. The image on the left is the emblem Ulmer generated from his mystory, leading to design of his wide image in

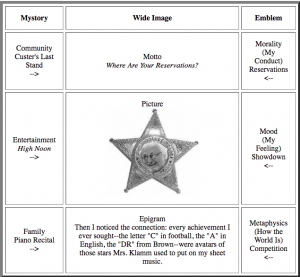

–Tenor (Themata): Catechism. The image on the left is the emblem Ulmer generated from his mystory, leading to design of his wide image in  3) The third question is Mood: given the necessity to act in that way, in a world of that character, how do I feel? Wabi-Sabi advises acceptance of the inevitable and appreciation of the cosmic order. Ulmer found his state of mind expressed in High Noon as a fable of duty: despite his contempt for the hypocritical community, the sheriff fought the gang of killers, after which he threw away the tin star. This gesture of discarding the badge of status determined the tin star as the icon of the emblem. In practice it is best to decide which popcycle story supplies the picture, and which question of the catechism that story answers, and the rest of the emblem follows from there.

3) The third question is Mood: given the necessity to act in that way, in a world of that character, how do I feel? Wabi-Sabi advises acceptance of the inevitable and appreciation of the cosmic order. Ulmer found his state of mind expressed in High Noon as a fable of duty: despite his contempt for the hypocritical community, the sheriff fought the gang of killers, after which he threw away the tin star. This gesture of discarding the badge of status determined the tin star as the icon of the emblem. In practice it is best to decide which popcycle story supplies the picture, and which question of the catechism that story answers, and the rest of the emblem follows from there. The Way to Rainy Mountain. Son of a White mother and Kiowa father, Momaday was raised on a reservation. His novel House Made of Dawn won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969. His autobiographical The Way to Rainy Mountain was assigned as relay modeling the micro form and overall structuring by means of signifiers repeating across levels of the popcycle. Rainy Mountain juxtaposes Kiowa myths Momaday learned from his grandmother; the actual history of the Kiowa symbolized in the myths; his personal recollections of his childhood on the reservation. The text manifests identification (with his grandmother Aho and his grandfather Mammedaty); the use of pattern (the unity of each section is created by the repetition of a detail within the exposition across the three discourses); the use of setting to express feeling (the memories of scenes from the reservation). Most important is the location of Momaday’s memories of childhood in the context of the traditional stories and actual history of his Community (Kiowa), thus bringing the three levels of his symbolic experience into contact–personal, historical, mythical (entertainment fictions in a modern point of view). The book is a collection of thirty-four three-paragraph units (plus introduction and epilogue) illustrated with drawings by Momaday’s father. Unit 3 is cited as example: the popcycle sequence is always the same: Mythology; History; Memory.

The Way to Rainy Mountain. Son of a White mother and Kiowa father, Momaday was raised on a reservation. His novel House Made of Dawn won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969. His autobiographical The Way to Rainy Mountain was assigned as relay modeling the micro form and overall structuring by means of signifiers repeating across levels of the popcycle. Rainy Mountain juxtaposes Kiowa myths Momaday learned from his grandmother; the actual history of the Kiowa symbolized in the myths; his personal recollections of his childhood on the reservation. The text manifests identification (with his grandmother Aho and his grandfather Mammedaty); the use of pattern (the unity of each section is created by the repetition of a detail within the exposition across the three discourses); the use of setting to express feeling (the memories of scenes from the reservation). Most important is the location of Momaday’s memories of childhood in the context of the traditional stories and actual history of his Community (Kiowa), thus bringing the three levels of his symbolic experience into contact–personal, historical, mythical (entertainment fictions in a modern point of view). The book is a collection of thirty-four three-paragraph units (plus introduction and epilogue) illustrated with drawings by Momaday’s father. Unit 3 is cited as example: the popcycle sequence is always the same: Mythology; History; Memory. III

III Maurice Sendak is best known for his Caldecott Medal winning illustrated children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963), made into

Maurice Sendak is best known for his Caldecott Medal winning illustrated children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963), made into  –Family (Personal): Composition of mystory usually begins with a memory from early childhood, life with the family. Up to three such memories are allowed, to avoid getting stuck deciding on one that is most important (that dilemma if it arises is resolved when the remaining slots are filled, following the rule what resembles assembles). Sendak proposed two memories: the first was one of his earliest, an encounter with one of the pedagogical objects Pasolini mentioned, a book his older sister received from her book club. The book was very thick with a hardcover of pale green with gold lettering. Although not yet able to read, Sendak was fascinated with the book and demanded to have it, creating so much commotion the parents made his sister give it to him. When he finally returned it to his sister it was in bad shape, including suffering from being licked all over.

–Family (Personal): Composition of mystory usually begins with a memory from early childhood, life with the family. Up to three such memories are allowed, to avoid getting stuck deciding on one that is most important (that dilemma if it arises is resolved when the remaining slots are filled, following the rule what resembles assembles). Sendak proposed two memories: the first was one of his earliest, an encounter with one of the pedagogical objects Pasolini mentioned, a book his older sister received from her book club. The book was very thick with a hardcover of pale green with gold lettering. Although not yet able to read, Sendak was fascinated with the book and demanded to have it, creating so much commotion the parents made his sister give it to him. When he finally returned it to his sister it was in bad shape, including suffering from being licked all over. I was eleven when I saw the movie, and I remember it vividly because of how intensely in frightened me. The moment I am talking about is the one when Dorothy is trapped by the Wicked Witch of the West, and the witch takes an hourglass and turns it over and says something horrible like, “When the sand runs out, you’re dead, honey.” Judy Garland is left alone in the room, and one of her best moments ever was her way of saying, “I’m frightened,” and then, as though that realization has just actually dawned on her, says it a second time, “I’m frightened.” I still remember how her hand went to her head–the way she had of fluttering her hand, her desperation was so convincing. There was no way out of that room, nothing she could do. And suddenly, in the witch’s crystal ball, she sees her Auntie Em, back in Kansas, standing in the yard and calling to her. And she rushes to the crystal ball, and stands over it and screams, “Auntie Em! Here I am!”

I was eleven when I saw the movie, and I remember it vividly because of how intensely in frightened me. The moment I am talking about is the one when Dorothy is trapped by the Wicked Witch of the West, and the witch takes an hourglass and turns it over and says something horrible like, “When the sand runs out, you’re dead, honey.” Judy Garland is left alone in the room, and one of her best moments ever was her way of saying, “I’m frightened,” and then, as though that realization has just actually dawned on her, says it a second time, “I’m frightened.” I still remember how her hand went to her head–the way she had of fluttering her hand, her desperation was so convincing. There was no way out of that room, nothing she could do. And suddenly, in the witch’s crystal ball, she sees her Auntie Em, back in Kansas, standing in the yard and calling to her. And she rushes to the crystal ball, and stands over it and screams, “Auntie Em! Here I am!” The major event of my childhood was the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932. That nightmare was probably the origin of my conviction that children can’t be shielded from frightening truths. Although I was only three, I remember intensely the details of the Lindbergh case. Lindbergh was our Prince Charles, and his wife was our Princess Di. I particularly remember a newspaper that had the front-page headline LINDBERGH BABY FOUND DEAD and a photograph of a scene in the woods with a black arrow pointing to something awful. I’ve since learned that Colonel Lindbergh threatened to sue if the New York Daily News didn’t have the morning edition pulled off the newsstands, so I guess not many people saw the picture. But I saw the picture.

The major event of my childhood was the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932. That nightmare was probably the origin of my conviction that children can’t be shielded from frightening truths. Although I was only three, I remember intensely the details of the Lindbergh case. Lindbergh was our Prince Charles, and his wife was our Princess Di. I particularly remember a newspaper that had the front-page headline LINDBERGH BABY FOUND DEAD and a photograph of a scene in the woods with a black arrow pointing to something awful. I’ve since learned that Colonel Lindbergh threatened to sue if the New York Daily News didn’t have the morning edition pulled off the newsstands, so I guess not many people saw the picture. But I saw the picture.

When it comes to the image of wide scope (four or five fundamental images structuring imagination, and central to the history of invention), the prototype is Einstein’s compass (received from his father as a gift at age four or five): the wide image is a compass for the existential positioning system of learning, to orient egents tracking the vector of invention.

When it comes to the image of wide scope (four or five fundamental images structuring imagination, and central to the history of invention), the prototype is Einstein’s compass (received from his father as a gift at age four or five): the wide image is a compass for the existential positioning system of learning, to orient egents tracking the vector of invention. Popcycle. Learning is a complex adaptive system, and an aspect of what we are exploring is a certain isomorphism transversing all such systems. Heuretic pedagogy is describable within a systems perspective, beginning with the

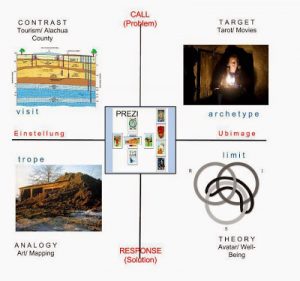

Popcycle. Learning is a complex adaptive system, and an aspect of what we are exploring is a certain isomorphism transversing all such systems. Heuretic pedagogy is describable within a systems perspective, beginning with the  –Mandala. A basic diagram (popcycle mandala) is used consistently throughout KE to map and correlate correspondences across the layers and levels of the popcycle-mystory-wide image as Interface for the Stack of digital civilization. The diagram is not original, but is appropriated from various fourfold system templates. The diagram below registers the CATTt of a seminar documented in Ulmer’s blog,

–Mandala. A basic diagram (popcycle mandala) is used consistently throughout KE to map and correlate correspondences across the layers and levels of the popcycle-mystory-wide image as Interface for the Stack of digital civilization. The diagram is not original, but is appropriated from various fourfold system templates. The diagram below registers the CATTt of a seminar documented in Ulmer’s blog,

History (School, Community): Young Joyce’s imagination was captured by the cause of Irish freedom, whose most prominent spokesman at the time was Charles Stewart Parnell, a national hero who suffered a tragic fall. “He was accused of adultery in the divorce suit of Captain O’Shea. At first it appeared that Parnell might weather this scandal, but a coalition of political enemies and devout Catholics ousted him from leadership of the Irish Parliamentary Party, and the rural population of Ireland turned against their hero with savage hatred” (Litz, 1972: 20). At Parnell’s funeral crowds tore to shreds the case in which the man’s coffin had been shipped in order to have a relic. Soon he became in the Irish imagination the type of the betrayed hero (21).

History (School, Community): Young Joyce’s imagination was captured by the cause of Irish freedom, whose most prominent spokesman at the time was Charles Stewart Parnell, a national hero who suffered a tragic fall. “He was accused of adultery in the divorce suit of Captain O’Shea. At first it appeared that Parnell might weather this scandal, but a coalition of political enemies and devout Catholics ousted him from leadership of the Irish Parliamentary Party, and the rural population of Ireland turned against their hero with savage hatred” (Litz, 1972: 20). At Parnell’s funeral crowds tore to shreds the case in which the man’s coffin had been shipped in order to have a relic. Soon he became in the Irish imagination the type of the betrayed hero (21). Career: At age eighteen Joyce published a refiew of Ibsen’s play, “When We Dead Awaken” in The Fortnightly Review. In a letter he sent to Ibsen, the student Joyce explained that while he promoted the dramatist’s work at every opportunity, he kept to himself the most important reasons for his admiration. “I did not say how what I could discern dimly of your life was my pride to see, how your battles inspired me–not the obvious material battle but those that were fought and won behind your forehead–how your willful resolution to wrest the secret from life gave me heart and how in your absolute indifference to public canons of art friends and shibboleths you walked in the light of your inward heroism” (Joyce, in Litz, 24).

Career: At age eighteen Joyce published a refiew of Ibsen’s play, “When We Dead Awaken” in The Fortnightly Review. In a letter he sent to Ibsen, the student Joyce explained that while he promoted the dramatist’s work at every opportunity, he kept to himself the most important reasons for his admiration. “I did not say how what I could discern dimly of your life was my pride to see, how your battles inspired me–not the obvious material battle but those that were fought and won behind your forehead–how your willful resolution to wrest the secret from life gave me heart and how in your absolute indifference to public canons of art friends and shibboleths you walked in the light of your inward heroism” (Joyce, in Litz, 24). Family Discourse: Narrative

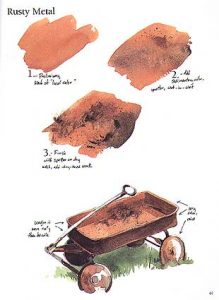

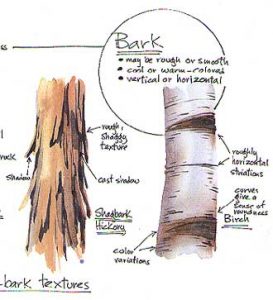

Family Discourse: Narrative One version of the assignment proposed that this documentation be entirely visual, to foreground the pictorial image in the way that the Family entry foregrounded the verbal image. However, this distinction is arbitrary since in both cases there is supposed to be a balance of words and graphics (adapting the forms to the medium of the Web).

One version of the assignment proposed that this documentation be entirely visual, to foreground the pictorial image in the way that the Family entry foregrounded the verbal image. However, this distinction is arbitrary since in both cases there is supposed to be a balance of words and graphics (adapting the forms to the medium of the Web).  Identity (Know Thyself)

Identity (Know Thyself)