Primal Scene: Curriculum

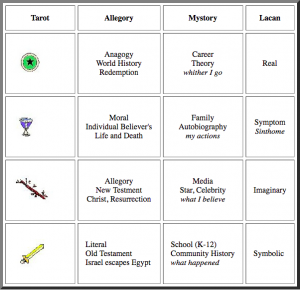

Mystory Curriculum. Mystory may be hermeneutic as well as heuretic, that is, it may be used to organize the curriculum, as part of a transition from literacy to electracy. It is persuasive in any case to find the image of wide scope as a structural principle operating in the arts. Examples of works across media manifesting wide images are assigned in a DH curriculum as exemplars and relays guiding egents in the design of their own wide images.

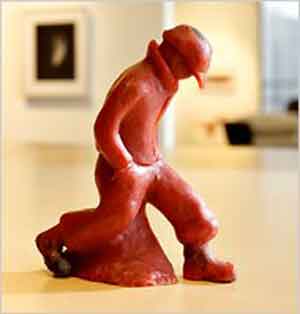

–Blade Runner 2049. A recent example is the Blade Runner sequel, the organizing role played by childhood memories in simulating human identity for replicants. The sequel narrative is motivated by the protagonist’s investigation of the memory of a carved wooden horse. This motif alludes formally and intertextually to the Orson Welles film, Citizen Kane-– the simulated documentary investigation into the enigma of Kane’s identity, his deathbed statement, “Rosebud.” The audience learns that “Rosebud” is the name of Kane’s sled, metonym of his childhood happiness. A konsult curriculum studies these works at several levels, to understand the relationship of lived experience to formal design.

–Blade Runner 2049. A recent example is the Blade Runner sequel, the organizing role played by childhood memories in simulating human identity for replicants. The sequel narrative is motivated by the protagonist’s investigation of the memory of a carved wooden horse. This motif alludes formally and intertextually to the Orson Welles film, Citizen Kane-– the simulated documentary investigation into the enigma of Kane’s identity, his deathbed statement, “Rosebud.” The audience learns that “Rosebud” is the name of Kane’s sled, metonym of his childhood happiness. A konsult curriculum studies these works at several levels, to understand the relationship of lived experience to formal design.

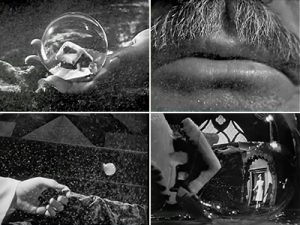

–Intertext. The seminar reads or screens the works mentioned here, analyzing how early memories function in both formal and thematic terms. Citizen Kane, often cited as the best American film ever made, is structured around a journalist’s attempt to solve the mystery of the dying Kane’s last word, “Rosebud.” The audience learns in the final scene that “Rosebud” is the name of Kane’s childhood sled, emblematic of his moment of happiness, in the genre of Proust’s madeleine, whose taste triggered a recollection of happiness whose source it was the goal of the novel to discover. The carved horse, the sled, are vehicles whose tenor the fictional works dramatize, to form hypothetical wide images.

–Murakami. Another example is 1Q84, by Haruki Murakami, one of whose characters (Tengo) is driven by an early childhood memory. “Murakami’s other protagonist, a writer and math tutor named Tengo, begins 1Q84 in something of an epileptic fit. These attacks strike regularly, we learn (and come to witness), triggered by the bubbling up to consciousness of Tengo’s first memory, witnessed from the crib: ‘His mother had taken off her blouse and dropped the shoulder strap of her white slip to let a man who was not his father suck on her breasts.’ Duly unrepressed, the memory paralyzes his limbs, cuts off his breathing, and occasions the novel’s single most eyebrow-raising sentence: ‘The tsunami’s liquid wall swallowed him whole.'”

–Murakami. Another example is 1Q84, by Haruki Murakami, one of whose characters (Tengo) is driven by an early childhood memory. “Murakami’s other protagonist, a writer and math tutor named Tengo, begins 1Q84 in something of an epileptic fit. These attacks strike regularly, we learn (and come to witness), triggered by the bubbling up to consciousness of Tengo’s first memory, witnessed from the crib: ‘His mother had taken off her blouse and dropped the shoulder strap of her white slip to let a man who was not his father suck on her breasts.’ Duly unrepressed, the memory paralyzes his limbs, cuts off his breathing, and occasions the novel’s single most eyebrow-raising sentence: ‘The tsunami’s liquid wall swallowed him whole.'”

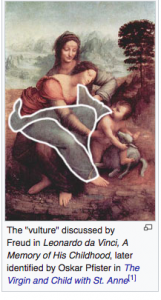

–Leonardo da Vinci. Sigmund Freud’s biographical study of Leonardo featured the one early memory Leonardo recorded in his journals. “It seems that it had been destined before that I should occupy myself so thoroughly with the vulture, for it comes to my mind as a very early memory, when I was still in the cradle, a vulture came down to me, he opened my mouth with his tail and struck me a few times with his tail against my lips.” We will return to these examples later. The point for now is just to note childhood early memories as an important motif in literature, cinema, philosophy, as resource for our heuretic curriculum. Such works are assigned, discussed, interpreted, for their own sake, but also as relays, poetics for design of egent wide images.

–Leonardo da Vinci. Sigmund Freud’s biographical study of Leonardo featured the one early memory Leonardo recorded in his journals. “It seems that it had been destined before that I should occupy myself so thoroughly with the vulture, for it comes to my mind as a very early memory, when I was still in the cradle, a vulture came down to me, he opened my mouth with his tail and struck me a few times with his tail against my lips.” We will return to these examples later. The point for now is just to note childhood early memories as an important motif in literature, cinema, philosophy, as resource for our heuretic curriculum. Such works are assigned, discussed, interpreted, for their own sake, but also as relays, poetics for design of egent wide images.

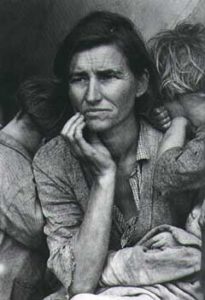

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times.

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times. This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”

This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”  Our first memories are visual ones. In memory life becomes a silent film. We all have in our minds an image which is the first, or one of the first, in our lives. That image is a sign, or to be exact, a linguistic sign. So if it is a linguistic sign it communicates or expresses something. I shall give you an example. The first image of my life is a white, transparent bind, which hangs–without moving, I believe–from a window which looks out on to a somewhat sad and dark lane. That blind terrifies me and fills me with anguish: not as something threatening and unpleasant but as something cosmic. In that blind the spirit of the middle-class house in Bologna where I was born is summed up and takes bodily form. Indeed the images which compete with the blind for chronological primacy are a room with an alcove (where my grandmother slept), heavy “proper” furniture, a carriage in the street which I wanted to climb into. These images are less painful than that of the blind, yet in them too there is concentrated that element of the cosmic which constitutes the petty bourgeois spirit of the world into which I was born. But if in the objects and things the images which have remained firmly in my memory (like those of an indelible dream) there is precipitated and concentrated the whole world of “memories,” which is recalled by those images in a single instant– if, that is to say, those object and those things are containers in which is stored a universe which I can extract and look at, then, at the same time, these objects and things are also something other than a container. . . . So their communication was essentially instructional. They taught me where I had been born, in what world I lived, and above all how to think about my birth and my life. Since it was a question of an unarticulated, fixed and incontrovertible pedagogic discourse, it could not be other–as we say today–than authoritarian and repressive. What that blind said to me and taught me did not admit (and does not admit) of rejoinders. No dialogue was possible or admissible with it, nor any act of self-education. That is why I believed that the whole world was the world which that blind taught me: that is to say, I thought that the whole world was “proper,” idealistic, sad and skeptical, a little vulgar–in short, petty bourgeois. (Pier Paolo Pasolini, Lutheran Letters, trans. Stuart Hood. Carcanet Press: New York, 1987).

Our first memories are visual ones. In memory life becomes a silent film. We all have in our minds an image which is the first, or one of the first, in our lives. That image is a sign, or to be exact, a linguistic sign. So if it is a linguistic sign it communicates or expresses something. I shall give you an example. The first image of my life is a white, transparent bind, which hangs–without moving, I believe–from a window which looks out on to a somewhat sad and dark lane. That blind terrifies me and fills me with anguish: not as something threatening and unpleasant but as something cosmic. In that blind the spirit of the middle-class house in Bologna where I was born is summed up and takes bodily form. Indeed the images which compete with the blind for chronological primacy are a room with an alcove (where my grandmother slept), heavy “proper” furniture, a carriage in the street which I wanted to climb into. These images are less painful than that of the blind, yet in them too there is concentrated that element of the cosmic which constitutes the petty bourgeois spirit of the world into which I was born. But if in the objects and things the images which have remained firmly in my memory (like those of an indelible dream) there is precipitated and concentrated the whole world of “memories,” which is recalled by those images in a single instant– if, that is to say, those object and those things are containers in which is stored a universe which I can extract and look at, then, at the same time, these objects and things are also something other than a container. . . . So their communication was essentially instructional. They taught me where I had been born, in what world I lived, and above all how to think about my birth and my life. Since it was a question of an unarticulated, fixed and incontrovertible pedagogic discourse, it could not be other–as we say today–than authoritarian and repressive. What that blind said to me and taught me did not admit (and does not admit) of rejoinders. No dialogue was possible or admissible with it, nor any act of self-education. That is why I believed that the whole world was the world which that blind taught me: that is to say, I thought that the whole world was “proper,” idealistic, sad and skeptical, a little vulgar–in short, petty bourgeois. (Pier Paolo Pasolini, Lutheran Letters, trans. Stuart Hood. Carcanet Press: New York, 1987). Here is Existential Positioning (EPS) in experience. How common is it to have an intuition of mortality during childhood? It is as if each person has to realize for him/herself individually what the sages codified in Ancient philosophy as ataraxy. Ataraxy is a state of mind in which the sage, realizing that s/he has no control over external events, decides to reduce her/his own desires. This ascetic view is associated with the stance that “philosophy is learning how to die.” Paradoxically, it may seem, philosophers insist that the realization that everyone dies is liberating. Since death is inevitable, why get so excited over one’s successes and failures in life? Of course, various response to this intuition are possible, such as carpe diem (seize the day).

Here is Existential Positioning (EPS) in experience. How common is it to have an intuition of mortality during childhood? It is as if each person has to realize for him/herself individually what the sages codified in Ancient philosophy as ataraxy. Ataraxy is a state of mind in which the sage, realizing that s/he has no control over external events, decides to reduce her/his own desires. This ascetic view is associated with the stance that “philosophy is learning how to die.” Paradoxically, it may seem, philosophers insist that the realization that everyone dies is liberating. Since death is inevitable, why get so excited over one’s successes and failures in life? Of course, various response to this intuition are possible, such as carpe diem (seize the day). A primal scene? The boy is eleven, starting seventh grade. His father explains that it is time to learn the value of work. He has arranged a job for his son with a friend whose name is Cutting and who owns a sheet metal shop. Every Saturday the boy rides his bicycle across town to Cutting’s Sheet Metal. The employees are done for the week at noon on Saturday. He has to arrive by noon so the boss can lock up, leaving the boy inside (he is too young to be trusted with a key). The job is to clean the shop — sweep the floor, gather up the tools and align them neatly in their designated places on the work benches, collect the remnants and clippings of the metal sheets scattered everywhere. It takes most of the afternoon to finish the chores. The shop is a cavernous open warehouse, with rows of heavy tables, the walls lined with shelves stacked to the distant ceiling with equipment, tools, metals. It is quiet, the stillness of dust motes swirling in the beams of sunlight filtered through the few windows high up near the roof, carving vectors through deep shadow. The sunlight catches the edges of a museum of blades, a taxonomy of every snipping snap slice chop saw hack rend rip cleave nip or severing machine. Half-shaped tin objects stand in rows behind piles of hammers and modelling frames. After so many weeks and months of Saturday noons the boy begins to lose touch with his former friends and companions, who go their separate ways.

A primal scene? The boy is eleven, starting seventh grade. His father explains that it is time to learn the value of work. He has arranged a job for his son with a friend whose name is Cutting and who owns a sheet metal shop. Every Saturday the boy rides his bicycle across town to Cutting’s Sheet Metal. The employees are done for the week at noon on Saturday. He has to arrive by noon so the boss can lock up, leaving the boy inside (he is too young to be trusted with a key). The job is to clean the shop — sweep the floor, gather up the tools and align them neatly in their designated places on the work benches, collect the remnants and clippings of the metal sheets scattered everywhere. It takes most of the afternoon to finish the chores. The shop is a cavernous open warehouse, with rows of heavy tables, the walls lined with shelves stacked to the distant ceiling with equipment, tools, metals. It is quiet, the stillness of dust motes swirling in the beams of sunlight filtered through the few windows high up near the roof, carving vectors through deep shadow. The sunlight catches the edges of a museum of blades, a taxonomy of every snipping snap slice chop saw hack rend rip cleave nip or severing machine. Half-shaped tin objects stand in rows behind piles of hammers and modelling frames. After so many weeks and months of Saturday noons the boy begins to lose touch with his former friends and companions, who go their separate ways. What happens then? The light and shadow of the industrial building open all at once onto a void, a black hole and white wall of divided worlds in this little infinite town: the official world of adults (parents, teachers, coaches, ministers, scout masters) that until then had constituted reality, and the unofficial world of his peers, whose existence he had only just discovered. Two completely different systems of virtue and vice, success and failure, winning and losing, visibility and invisibility, were enforced in these realms: systems Not only different, but opposite and in conflict. What earned admiration and respect in one was inversely judged in the other. He could not have articulated the revelation so abstractly then. The unexpected aspect of this scene is the sense of abandonment, solitary isolation, that overcomes the child, a spilling out or abjection, an absolute exhaling of substance, followed soon after by the inhaled relief of knowing that it doesn’t matter, since everyone and everything dies everywhere the same death.

What happens then? The light and shadow of the industrial building open all at once onto a void, a black hole and white wall of divided worlds in this little infinite town: the official world of adults (parents, teachers, coaches, ministers, scout masters) that until then had constituted reality, and the unofficial world of his peers, whose existence he had only just discovered. Two completely different systems of virtue and vice, success and failure, winning and losing, visibility and invisibility, were enforced in these realms: systems Not only different, but opposite and in conflict. What earned admiration and respect in one was inversely judged in the other. He could not have articulated the revelation so abstractly then. The unexpected aspect of this scene is the sense of abandonment, solitary isolation, that overcomes the child, a spilling out or abjection, an absolute exhaling of substance, followed soon after by the inhaled relief of knowing that it doesn’t matter, since everyone and everything dies everywhere the same death.

History (School, Community): Young Joyce’s imagination was captured by the cause of Irish freedom, whose most prominent spokesman at the time was Charles Stewart Parnell, a national hero who suffered a tragic fall. “He was accused of adultery in the divorce suit of Captain O’Shea. At first it appeared that Parnell might weather this scandal, but a coalition of political enemies and devout Catholics ousted him from leadership of the Irish Parliamentary Party, and the rural population of Ireland turned against their hero with savage hatred” (Litz, 1972: 20). At Parnell’s funeral crowds tore to shreds the case in which the man’s coffin had been shipped in order to have a relic. Soon he became in the Irish imagination the type of the betrayed hero (21).

History (School, Community): Young Joyce’s imagination was captured by the cause of Irish freedom, whose most prominent spokesman at the time was Charles Stewart Parnell, a national hero who suffered a tragic fall. “He was accused of adultery in the divorce suit of Captain O’Shea. At first it appeared that Parnell might weather this scandal, but a coalition of political enemies and devout Catholics ousted him from leadership of the Irish Parliamentary Party, and the rural population of Ireland turned against their hero with savage hatred” (Litz, 1972: 20). At Parnell’s funeral crowds tore to shreds the case in which the man’s coffin had been shipped in order to have a relic. Soon he became in the Irish imagination the type of the betrayed hero (21). Career: At age eighteen Joyce published a refiew of Ibsen’s play, “When We Dead Awaken” in The Fortnightly Review. In a letter he sent to Ibsen, the student Joyce explained that while he promoted the dramatist’s work at every opportunity, he kept to himself the most important reasons for his admiration. “I did not say how what I could discern dimly of your life was my pride to see, how your battles inspired me–not the obvious material battle but those that were fought and won behind your forehead–how your willful resolution to wrest the secret from life gave me heart and how in your absolute indifference to public canons of art friends and shibboleths you walked in the light of your inward heroism” (Joyce, in Litz, 24).

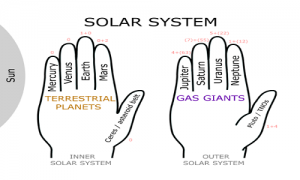

Career: At age eighteen Joyce published a refiew of Ibsen’s play, “When We Dead Awaken” in The Fortnightly Review. In a letter he sent to Ibsen, the student Joyce explained that while he promoted the dramatist’s work at every opportunity, he kept to himself the most important reasons for his admiration. “I did not say how what I could discern dimly of your life was my pride to see, how your battles inspired me–not the obvious material battle but those that were fought and won behind your forehead–how your willful resolution to wrest the secret from life gave me heart and how in your absolute indifference to public canons of art friends and shibboleths you walked in the light of your inward heroism” (Joyce, in Litz, 24). 2) Memory Palace. Konsult externalizes and augments mental modeling, including cognitive mapping, the capability of proprioception fundamental to orientation in space and time. A feature of apparatus shift is called innervation (facilitation)–referring to the neurological changes associated with brain/mind adaptation to new technologies. In Phaedrus (the first discourse on method of literacy), Socrates warned his pupil, Phaedrus (who came to his tutorial session with a cheat-sheet up his sleeve of the text he was supposed to memorize) that writing would destroy his memory. Pedagogy in the epoch of manuscript technology involved two interdependent practices: composition of a commonplace book (florilegia), organized by topics (topoi), consisting of methods for generating various genres along with archives of relevant information and resources;

2) Memory Palace. Konsult externalizes and augments mental modeling, including cognitive mapping, the capability of proprioception fundamental to orientation in space and time. A feature of apparatus shift is called innervation (facilitation)–referring to the neurological changes associated with brain/mind adaptation to new technologies. In Phaedrus (the first discourse on method of literacy), Socrates warned his pupil, Phaedrus (who came to his tutorial session with a cheat-sheet up his sleeve of the text he was supposed to memorize) that writing would destroy his memory. Pedagogy in the epoch of manuscript technology involved two interdependent practices: composition of a commonplace book (florilegia), organized by topics (topoi), consisting of methods for generating various genres along with archives of relevant information and resources;  –GPS/EPS. The comparable warning today is that

–GPS/EPS. The comparable warning today is that

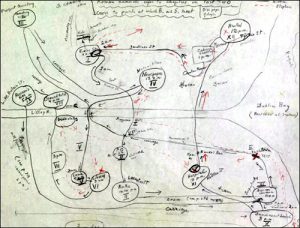

The creative individual pursues (or is pursued by) a number of dominant metaphors. These figures are images of wide scope, rich, and susceptible to considerable exploration, exposing the investigator to aspects of phenomena that might otherwise remain invisible to him. Often the key to the individual’s most important innovations inhere in these images. In Darwin’s case, the most fecund metaphor was the branching tree of evolution, on which he could trace the rise and fate of various species. Gruber’s students have uncovered other such metaphors of wide scope. William James had a penchant for viewing mental processes as a stream or river, rather than in terms of the associationist images of a train or a chain. Any consideration of John Locke should focus on his falconer, whose release of a bird symbolized the quest for human knowledge. Finally, in conveying his own emerging view of the creative process, Gruber finds himiself attracted to the Mosaic image of the bush that is always burning but never consumed. (Howard Gardner, Art, Mind, and Brain: A Cognitive Approach to Creativity).

The creative individual pursues (or is pursued by) a number of dominant metaphors. These figures are images of wide scope, rich, and susceptible to considerable exploration, exposing the investigator to aspects of phenomena that might otherwise remain invisible to him. Often the key to the individual’s most important innovations inhere in these images. In Darwin’s case, the most fecund metaphor was the branching tree of evolution, on which he could trace the rise and fate of various species. Gruber’s students have uncovered other such metaphors of wide scope. William James had a penchant for viewing mental processes as a stream or river, rather than in terms of the associationist images of a train or a chain. Any consideration of John Locke should focus on his falconer, whose release of a bird symbolized the quest for human knowledge. Finally, in conveying his own emerging view of the creative process, Gruber finds himiself attracted to the Mosaic image of the bush that is always burning but never consumed. (Howard Gardner, Art, Mind, and Brain: A Cognitive Approach to Creativity). –Steven Spielberg. Sarah Boxer asked Steven Spielberg to recall his earliest visual experience. He found one from the age of 3.

–Steven Spielberg. Sarah Boxer asked Steven Spielberg to recall his earliest visual experience. He found one from the age of 3. 6) Memory Exercise: Kandinsky. As illustrated by the careers of productive people, at some point an interviewer will ask about an early memory from childhood. Mystory may adopt such interviews–the kind of things people want to know about the sources and motivations of creativity–as a guide to identify similar resources in one’s own biography to bring into the wide image matrix. Exercise: read an interview with a creative person of interest, inventory the questions asked, and answer them in your own case.

6) Memory Exercise: Kandinsky. As illustrated by the careers of productive people, at some point an interviewer will ask about an early memory from childhood. Mystory may adopt such interviews–the kind of things people want to know about the sources and motivations of creativity–as a guide to identify similar resources in one’s own biography to bring into the wide image matrix. Exercise: read an interview with a creative person of interest, inventory the questions asked, and answer them in your own case.