TPE: Emblem, Wabi Sabi 2

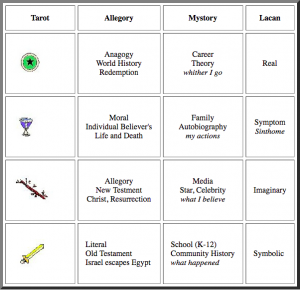

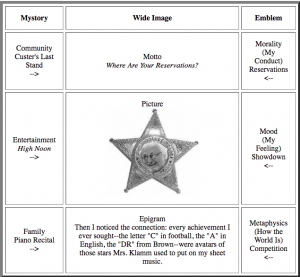

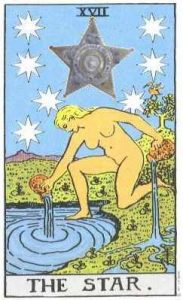

–Tenor (Themata): Catechism. The image on the left is the emblem Ulmer generated from his mystory, leading to design of his wide image in Noon Star. The formal rules from Koren’s relay generates theopraxesis by requiring that the answer to the catechism questions must be derived from one of the popcycle stories, each story used once only. The three capabilities are expressed in Wabi-Sabi by three M’s (resonating with the H’MMM disciplines): Metaphysics (Theoria); Morality (Praxis); Mood (Poiesis). Egents ask themselves:

–Tenor (Themata): Catechism. The image on the left is the emblem Ulmer generated from his mystory, leading to design of his wide image in Noon Star. The formal rules from Koren’s relay generates theopraxesis by requiring that the answer to the catechism questions must be derived from one of the popcycle stories, each story used once only. The three capabilities are expressed in Wabi-Sabi by three M’s (resonating with the H’MMM disciplines): Metaphysics (Theoria); Morality (Praxis); Mood (Poiesis). Egents ask themselves:

1) which of the popcycle stories, received as a fable (parable), expresses their understanding of how the world works, the character of reality. The Japanese tradition answers, “Things are either devolving toward, or evolving from, nothingness.” For Ulmer, the Family story of the botched piano recital, the red star (not gold or silver) on the sheet music, is a parable of a reality in which one is continuously judged in endless competitions. His epigram describes that condition.

2) Morality (Spiritual Values): which popcyle story is a fable of how one must act, given the character of reality? Wabi-Sabi proposes to get rid of what is unnecessary, ignore material hierarchy. For Ulmer, Custer’s foolish ambition serves as a negative example, a fable warning against Custer’s desire for glory. Ulmer’s motto expresses his lesson: Where are your Reservations?

3) The third question is Mood: given the necessity to act in that way, in a world of that character, how do I feel? Wabi-Sabi advises acceptance of the inevitable and appreciation of the cosmic order. Ulmer found his state of mind expressed in High Noon as a fable of duty: despite his contempt for the hypocritical community, the sheriff fought the gang of killers, after which he threw away the tin star. This gesture of discarding the badge of status determined the tin star as the icon of the emblem. In practice it is best to decide which popcycle story supplies the picture, and which question of the catechism that story answers, and the rest of the emblem follows from there.

3) The third question is Mood: given the necessity to act in that way, in a world of that character, how do I feel? Wabi-Sabi advises acceptance of the inevitable and appreciation of the cosmic order. Ulmer found his state of mind expressed in High Noon as a fable of duty: despite his contempt for the hypocritical community, the sheriff fought the gang of killers, after which he threw away the tin star. This gesture of discarding the badge of status determined the tin star as the icon of the emblem. In practice it is best to decide which popcycle story supplies the picture, and which question of the catechism that story answers, and the rest of the emblem follows from there.

The wide image has no innate form, and is not confined to emblem poetics. It is inchoate, accessed intuitively, acquired during the early years of embodied visceral education. It may take many forms and manifest itself within the creative production of an egent. The heuretic frame of electrate pedagogy moves egents through the transition from a condition of privation, Steresis, impotence, potentiality of capability (Dunamis, Virtuality) into Energeia, Actualization, raising consciousness of their positioning and disposition relative to the archive of world culture recording in infinite variation the unfolding of the work of realization of life and death. Konsult is equipment for living (Kenneth Burke), thus, empowering in principle the egent with the resources of civilization available for a fatal encounter with disaster.

The Way to Rainy Mountain. Son of a White mother and Kiowa father, Momaday was raised on a reservation. His novel House Made of Dawn won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969. His autobiographical The Way to Rainy Mountain was assigned as relay modeling the micro form and overall structuring by means of signifiers repeating across levels of the popcycle. Rainy Mountain juxtaposes Kiowa myths Momaday learned from his grandmother; the actual history of the Kiowa symbolized in the myths; his personal recollections of his childhood on the reservation. The text manifests identification (with his grandmother Aho and his grandfather Mammedaty); the use of pattern (the unity of each section is created by the repetition of a detail within the exposition across the three discourses); the use of setting to express feeling (the memories of scenes from the reservation). Most important is the location of Momaday’s memories of childhood in the context of the traditional stories and actual history of his Community (Kiowa), thus bringing the three levels of his symbolic experience into contact–personal, historical, mythical (entertainment fictions in a modern point of view). The book is a collection of thirty-four three-paragraph units (plus introduction and epilogue) illustrated with drawings by Momaday’s father. Unit 3 is cited as example: the popcycle sequence is always the same: Mythology; History; Memory.

The Way to Rainy Mountain. Son of a White mother and Kiowa father, Momaday was raised on a reservation. His novel House Made of Dawn won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969. His autobiographical The Way to Rainy Mountain was assigned as relay modeling the micro form and overall structuring by means of signifiers repeating across levels of the popcycle. Rainy Mountain juxtaposes Kiowa myths Momaday learned from his grandmother; the actual history of the Kiowa symbolized in the myths; his personal recollections of his childhood on the reservation. The text manifests identification (with his grandmother Aho and his grandfather Mammedaty); the use of pattern (the unity of each section is created by the repetition of a detail within the exposition across the three discourses); the use of setting to express feeling (the memories of scenes from the reservation). Most important is the location of Momaday’s memories of childhood in the context of the traditional stories and actual history of his Community (Kiowa), thus bringing the three levels of his symbolic experience into contact–personal, historical, mythical (entertainment fictions in a modern point of view). The book is a collection of thirty-four three-paragraph units (plus introduction and epilogue) illustrated with drawings by Momaday’s father. Unit 3 is cited as example: the popcycle sequence is always the same: Mythology; History; Memory. III

III

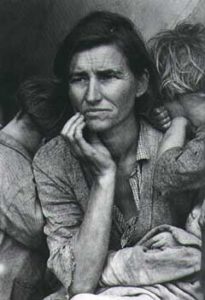

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times.

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times. This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”

This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”  Everyday life is a dimension of the lifeworld addressed in the tradition of Arts & Letters disciplines dating back to Marx’s commentaries on the revolutions in France (Paris) beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century. The issue is central to electracy, in that the digital apparatus is associated with the rise of the industrial city. The primary institutional condition to be remedied through a new (image) metaphysics is the impoverishment of everyday life codified in the concepts of alienation, reification, objectification. Marx diagnosed the problem as due to the division of labor, and the new cultural and social environment created by the commodity form in market capitalism under bourgeois hegemony. Life in the industrial city became “uncanny,” due to a discontinuity, disjunction, between individual agency and collective events. An equivalent of the Unconscious opened within culture, a return of the repressed in which citizens suffered the consequences of their collective actions as if visited upon them by divine powers (commodity fetishism). “Routine” in this context is the habituation of daily ritual that must be dispersed by means of shock arts devices of estrangement (defamiliarization).

Everyday life is a dimension of the lifeworld addressed in the tradition of Arts & Letters disciplines dating back to Marx’s commentaries on the revolutions in France (Paris) beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century. The issue is central to electracy, in that the digital apparatus is associated with the rise of the industrial city. The primary institutional condition to be remedied through a new (image) metaphysics is the impoverishment of everyday life codified in the concepts of alienation, reification, objectification. Marx diagnosed the problem as due to the division of labor, and the new cultural and social environment created by the commodity form in market capitalism under bourgeois hegemony. Life in the industrial city became “uncanny,” due to a discontinuity, disjunction, between individual agency and collective events. An equivalent of the Unconscious opened within culture, a return of the repressed in which citizens suffered the consequences of their collective actions as if visited upon them by divine powers (commodity fetishism). “Routine” in this context is the habituation of daily ritual that must be dispersed by means of shock arts devices of estrangement (defamiliarization).

Situation.What does it mean to approach Everyday Life with an aesthetic attitude? There is nothing novel about framing one’s quotidian roles in some state of mind — wisdom, science, religion. As practice, the aesthetic attitude is included within a situation, adding to the intentionality of some project the distance that generates aura of signification. “Situation” is a guideword, evoking the existentialist point that circumstances become a situation when considered from the point of view of one’s “project,” the goals of a practice, encountering a scene not indifferently but according to its affordances for some purpose. In a Visit (for konsult) this project or purpose is given an aesthetic frame.

Situation.What does it mean to approach Everyday Life with an aesthetic attitude? There is nothing novel about framing one’s quotidian roles in some state of mind — wisdom, science, religion. As practice, the aesthetic attitude is included within a situation, adding to the intentionality of some project the distance that generates aura of signification. “Situation” is a guideword, evoking the existentialist point that circumstances become a situation when considered from the point of view of one’s “project,” the goals of a practice, encountering a scene not indifferently but according to its affordances for some purpose. In a Visit (for konsult) this project or purpose is given an aesthetic frame.

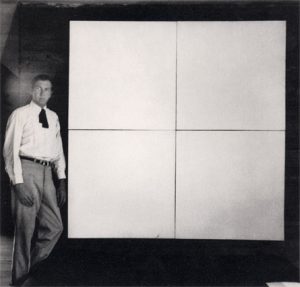

But not yet have we solved the incantation of this whiteness, and learned why it appeals with such power to the soul; and more strange and far more portentous–why, as we have seen, it is at once the most meaning symbol of spiritual things, nay, the very veil of the Christian’s Deity; and yet should be as it is, the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind.

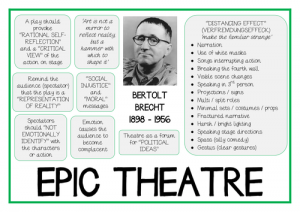

But not yet have we solved the incantation of this whiteness, and learned why it appeals with such power to the soul; and more strange and far more portentous–why, as we have seen, it is at once the most meaning symbol of spiritual things, nay, the very veil of the Christian’s Deity; and yet should be as it is, the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind. “Gest” is not supposed to mean gesticulation: it is not a matter of explana-tory or emphatic movements of the hands, but of overall attitudes. A language is gestic when it is grounded in a gest and conveys particular attitudes adopted by the speaker towards other men. The sentence “pluck the eye that offends thee out” is less effective from the gestic point of view than “if thine eve offend thee, pluck it out.” The latter starts by pre-senting the eye, and the first clause has the definite gest of making an assumption; the main clause then comes as a surprise, a piece of advice, and a relief.

“Gest” is not supposed to mean gesticulation: it is not a matter of explana-tory or emphatic movements of the hands, but of overall attitudes. A language is gestic when it is grounded in a gest and conveys particular attitudes adopted by the speaker towards other men. The sentence “pluck the eye that offends thee out” is less effective from the gestic point of view than “if thine eve offend thee, pluck it out.” The latter starts by pre-senting the eye, and the first clause has the definite gest of making an assumption; the main clause then comes as a surprise, a piece of advice, and a relief. Suppose that the musician composing a cantata on Lenin’s death has to reproduce his own attitude to the class struggle. As far as the gest goes, there are a number of different ways in which the report of Lenin’s death can be set. A certain dignity of presentation means little, since where death is involved this could also be held to be fitting in the case of an enemy. Anger at ‘the blind workings of providence’ cutting short the lives of the best members of the community would not be a communist gest; nor would a wise resignation to “life’s irony”; for the gest of communists mourning a communist is a very special one. The musician’s attitude to his text, the spokesman’s to his report, shows the extent of his political, and so of his human maturity. A man’s stature is shown by what he mourns and in what way he mourns it. To raise mourning to a high plane, to make it into an element of social progress: that is an artistic task.

Suppose that the musician composing a cantata on Lenin’s death has to reproduce his own attitude to the class struggle. As far as the gest goes, there are a number of different ways in which the report of Lenin’s death can be set. A certain dignity of presentation means little, since where death is involved this could also be held to be fitting in the case of an enemy. Anger at ‘the blind workings of providence’ cutting short the lives of the best members of the community would not be a communist gest; nor would a wise resignation to “life’s irony”; for the gest of communists mourning a communist is a very special one. The musician’s attitude to his text, the spokesman’s to his report, shows the extent of his political, and so of his human maturity. A man’s stature is shown by what he mourns and in what way he mourns it. To raise mourning to a high plane, to make it into an element of social progress: that is an artistic task.