Primal Scene: Curriculum

Mystory Curriculum. Mystory may be hermeneutic as well as heuretic, that is, it may be used to organize the curriculum, as part of a transition from literacy to electracy. It is persuasive in any case to find the image of wide scope as a structural principle operating in the arts. Examples of works across media manifesting wide images are assigned in a DH curriculum as exemplars and relays guiding egents in the design of their own wide images.

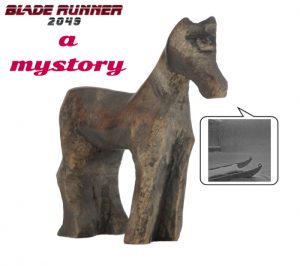

–Blade Runner 2049. A recent example is the Blade Runner sequel, the organizing role played by childhood memories in simulating human identity for replicants. The sequel narrative is motivated by the protagonist’s investigation of the memory of a carved wooden horse. This motif alludes formally and intertextually to the Orson Welles film, Citizen Kane-– the simulated documentary investigation into the enigma of Kane’s identity, his deathbed statement, “Rosebud.” The audience learns that “Rosebud” is the name of Kane’s sled, metonym of his childhood happiness. A konsult curriculum studies these works at several levels, to understand the relationship of lived experience to formal design.

–Blade Runner 2049. A recent example is the Blade Runner sequel, the organizing role played by childhood memories in simulating human identity for replicants. The sequel narrative is motivated by the protagonist’s investigation of the memory of a carved wooden horse. This motif alludes formally and intertextually to the Orson Welles film, Citizen Kane-– the simulated documentary investigation into the enigma of Kane’s identity, his deathbed statement, “Rosebud.” The audience learns that “Rosebud” is the name of Kane’s sled, metonym of his childhood happiness. A konsult curriculum studies these works at several levels, to understand the relationship of lived experience to formal design.

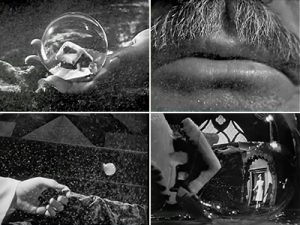

–Intertext. The seminar reads or screens the works mentioned here, analyzing how early memories function in both formal and thematic terms. Citizen Kane, often cited as the best American film ever made, is structured around a journalist’s attempt to solve the mystery of the dying Kane’s last word, “Rosebud.” The audience learns in the final scene that “Rosebud” is the name of Kane’s childhood sled, emblematic of his moment of happiness, in the genre of Proust’s madeleine, whose taste triggered a recollection of happiness whose source it was the goal of the novel to discover. The carved horse, the sled, are vehicles whose tenor the fictional works dramatize, to form hypothetical wide images.

–Murakami. Another example is 1Q84, by Haruki Murakami, one of whose characters (Tengo) is driven by an early childhood memory. “Murakami’s other protagonist, a writer and math tutor named Tengo, begins 1Q84 in something of an epileptic fit. These attacks strike regularly, we learn (and come to witness), triggered by the bubbling up to consciousness of Tengo’s first memory, witnessed from the crib: ‘His mother had taken off her blouse and dropped the shoulder strap of her white slip to let a man who was not his father suck on her breasts.’ Duly unrepressed, the memory paralyzes his limbs, cuts off his breathing, and occasions the novel’s single most eyebrow-raising sentence: ‘The tsunami’s liquid wall swallowed him whole.'”

–Murakami. Another example is 1Q84, by Haruki Murakami, one of whose characters (Tengo) is driven by an early childhood memory. “Murakami’s other protagonist, a writer and math tutor named Tengo, begins 1Q84 in something of an epileptic fit. These attacks strike regularly, we learn (and come to witness), triggered by the bubbling up to consciousness of Tengo’s first memory, witnessed from the crib: ‘His mother had taken off her blouse and dropped the shoulder strap of her white slip to let a man who was not his father suck on her breasts.’ Duly unrepressed, the memory paralyzes his limbs, cuts off his breathing, and occasions the novel’s single most eyebrow-raising sentence: ‘The tsunami’s liquid wall swallowed him whole.'”

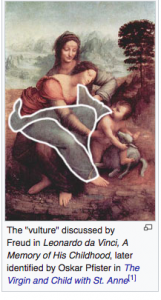

–Leonardo da Vinci. Sigmund Freud’s biographical study of Leonardo featured the one early memory Leonardo recorded in his journals. “It seems that it had been destined before that I should occupy myself so thoroughly with the vulture, for it comes to my mind as a very early memory, when I was still in the cradle, a vulture came down to me, he opened my mouth with his tail and struck me a few times with his tail against my lips.” We will return to these examples later. The point for now is just to note childhood early memories as an important motif in literature, cinema, philosophy, as resource for our heuretic curriculum. Such works are assigned, discussed, interpreted, for their own sake, but also as relays, poetics for design of egent wide images.

–Leonardo da Vinci. Sigmund Freud’s biographical study of Leonardo featured the one early memory Leonardo recorded in his journals. “It seems that it had been destined before that I should occupy myself so thoroughly with the vulture, for it comes to my mind as a very early memory, when I was still in the cradle, a vulture came down to me, he opened my mouth with his tail and struck me a few times with his tail against my lips.” We will return to these examples later. The point for now is just to note childhood early memories as an important motif in literature, cinema, philosophy, as resource for our heuretic curriculum. Such works are assigned, discussed, interpreted, for their own sake, but also as relays, poetics for design of egent wide images.

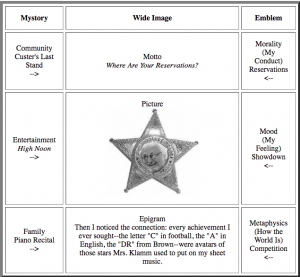

–Tenor (Themata): Catechism. The image on the left is the emblem Ulmer generated from his mystory, leading to design of his wide image in

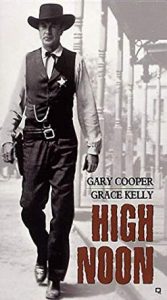

–Tenor (Themata): Catechism. The image on the left is the emblem Ulmer generated from his mystory, leading to design of his wide image in  3) The third question is Mood: given the necessity to act in that way, in a world of that character, how do I feel? Wabi-Sabi advises acceptance of the inevitable and appreciation of the cosmic order. Ulmer found his state of mind expressed in High Noon as a fable of duty: despite his contempt for the hypocritical community, the sheriff fought the gang of killers, after which he threw away the tin star. This gesture of discarding the badge of status determined the tin star as the icon of the emblem. In practice it is best to decide which popcycle story supplies the picture, and which question of the catechism that story answers, and the rest of the emblem follows from there.

3) The third question is Mood: given the necessity to act in that way, in a world of that character, how do I feel? Wabi-Sabi advises acceptance of the inevitable and appreciation of the cosmic order. Ulmer found his state of mind expressed in High Noon as a fable of duty: despite his contempt for the hypocritical community, the sheriff fought the gang of killers, after which he threw away the tin star. This gesture of discarding the badge of status determined the tin star as the icon of the emblem. In practice it is best to decide which popcycle story supplies the picture, and which question of the catechism that story answers, and the rest of the emblem follows from there. –How an Image becomes Wide. Koren demonstrates how a detail of the world is selected as a vehicle for a poetic image: for example, a worn shingle on an old hut, with a streak of rust descending from an iron nail. The tenor (theme) of this vehicle is coded in Japanese traditional culture, relative to the wisdom metaphysics of Buddhism, to express an existential insight into time and entropy known as wabi-sabi. “Wabi-Sabi can be called a ‘comprehensive’ aesthetic system. Its world view, or universe, is self-referential. It provides an integrated approach to the ultimate nature of existence (metaphysics), sacred knowledge (spirituality), emotional well-being (state of mind), behavior (morality), and the look and feel of things (materiality)” (Koren, 41). The instruction was not to seek Wabi-Sabi in one’s own experience, but the equivalent, the mood and atmosphere, to find one’s personal version of what was modeled in Japanese tradition. The folk traditions of Blues into Jazz in global Creole syncretism (mufarse into tango, saudade into samba) is central to the thymotic and erotic dimension of world materialized in digital electracy. Koren’s analysis demonstrates how to expand the two-part vehicle and tenor of image into a six-part inventory. Students generated their emblems productive of wide image by answer six questions posed by Koren: three for vehicle; three for tenor. The three questions addressing tenor (themata) are the same three articulated in the catechism of modernism, directing theopraxesis. One implication, to be developed further, is that the system of capabilities is not confined to the Western Tradition, but functions globally across cultures and civilizations.

–How an Image becomes Wide. Koren demonstrates how a detail of the world is selected as a vehicle for a poetic image: for example, a worn shingle on an old hut, with a streak of rust descending from an iron nail. The tenor (theme) of this vehicle is coded in Japanese traditional culture, relative to the wisdom metaphysics of Buddhism, to express an existential insight into time and entropy known as wabi-sabi. “Wabi-Sabi can be called a ‘comprehensive’ aesthetic system. Its world view, or universe, is self-referential. It provides an integrated approach to the ultimate nature of existence (metaphysics), sacred knowledge (spirituality), emotional well-being (state of mind), behavior (morality), and the look and feel of things (materiality)” (Koren, 41). The instruction was not to seek Wabi-Sabi in one’s own experience, but the equivalent, the mood and atmosphere, to find one’s personal version of what was modeled in Japanese tradition. The folk traditions of Blues into Jazz in global Creole syncretism (mufarse into tango, saudade into samba) is central to the thymotic and erotic dimension of world materialized in digital electracy. Koren’s analysis demonstrates how to expand the two-part vehicle and tenor of image into a six-part inventory. Students generated their emblems productive of wide image by answer six questions posed by Koren: three for vehicle; three for tenor. The three questions addressing tenor (themata) are the same three articulated in the catechism of modernism, directing theopraxesis. One implication, to be developed further, is that the system of capabilities is not confined to the Western Tradition, but functions globally across cultures and civilizations. –Poetics: Image expanded into Emblem. The expanded image consists of two registers: material; metaphysical. Working with the narratives generated in composition of mystory, students must commit to one pedagogical object (magic tool), some detail found in at least one of the diegesis of the popcycle, to serve as logo or brand icon for the wide image. In Ulmer’s case (Noon Star), the repeating detail (like the dogs repeating in Momaday’s section III) was a five-pointed star: Family memory (the red star on his sheet music of the march, Garry Owen; Entertainment mythology (the film High Noon, Gary Cooper as Will Kane, discarding his sheriff’s star in the dirt after the gun fight); Community history (“General” Custer’s badge of rank, and Indian name, Son of the Morning Star). The three material questions are: 1) what is the prop/ icon? Ulmer chose the tin star sheriff’s badge to represent this materiality. 2) What are its attributes? (what mood or atmosphere is expressed that distinguishes this icon from its archetype, configuring it specifically for me. The context of High Noon star thrown in the dirt expresses rejection and disgust with the hypocritical authority symbolized in the badge. 3) Archetype: what is the conventional meaning associated with this icon in the archive? (the five-pointed star has an extensive presence throughout many cultures).

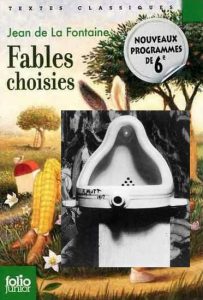

–Poetics: Image expanded into Emblem. The expanded image consists of two registers: material; metaphysical. Working with the narratives generated in composition of mystory, students must commit to one pedagogical object (magic tool), some detail found in at least one of the diegesis of the popcycle, to serve as logo or brand icon for the wide image. In Ulmer’s case (Noon Star), the repeating detail (like the dogs repeating in Momaday’s section III) was a five-pointed star: Family memory (the red star on his sheet music of the march, Garry Owen; Entertainment mythology (the film High Noon, Gary Cooper as Will Kane, discarding his sheriff’s star in the dirt after the gun fight); Community history (“General” Custer’s badge of rank, and Indian name, Son of the Morning Star). The three material questions are: 1) what is the prop/ icon? Ulmer chose the tin star sheriff’s badge to represent this materiality. 2) What are its attributes? (what mood or atmosphere is expressed that distinguishes this icon from its archetype, configuring it specifically for me. The context of High Noon star thrown in the dirt expresses rejection and disgust with the hypocritical authority symbolized in the badge. 3) Archetype: what is the conventional meaning associated with this icon in the archive? (the five-pointed star has an extensive presence throughout many cultures). –Fable: What resources are available for inquiry and expression in the conditions after Nietzsche, the history of an error, after the simultaneous withdrawal of the true world and the apparent world along with it? The time is noon (the shortest shadow). What remains is fable, Nietzsche said. What are the possibilities of fable as genre? Duchamp improvised one approach, perhaps not even yet fully appreciated. His Readymades are fables, albeit weak (faible) fables, in that they provide the illustrations only (the emblems, impresas). He intimated his variation on the mode with his most notorious instance, whose title “Fountain” translates “La Fontaine,” antonomasia between common and proper noun, evoking the name of the author of many fables in the common “fountain,” itself a euphemistic title for a urinal. Ulmer’s collage of the urinal with a cover of La Fontaine’s book make the joke explicit. Duchamp’s commitment to the punning bachelor machine logic central to modernism is well known. He acknowledged his attendance at a performance of a stage adaptation of Raymond Roussel’s 1910 novel Impressions of Africa as a turning point in his career (Roussel’s method of composition used generative puns). It has been suggested that some of the Readymades at least are comments on dreams described in Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, hence that they use rebus methods (visualizations evoking words). Freud noted, for example, that many dreams are triggered when sleepers experience the need to urinate (the dream allows sleep to continue briefly). The text of the fabled fountain is provided by its history, being as it is the most influential (if not the “best”) art work of the twentieth century, including its status as a prank, and all the manipulations Duchamp performed to put the image of La Fontaine into circulation, recorded in Thierry De Duve’s Kant After Duchamp. What is the moral of the readymade fable?

–Fable: What resources are available for inquiry and expression in the conditions after Nietzsche, the history of an error, after the simultaneous withdrawal of the true world and the apparent world along with it? The time is noon (the shortest shadow). What remains is fable, Nietzsche said. What are the possibilities of fable as genre? Duchamp improvised one approach, perhaps not even yet fully appreciated. His Readymades are fables, albeit weak (faible) fables, in that they provide the illustrations only (the emblems, impresas). He intimated his variation on the mode with his most notorious instance, whose title “Fountain” translates “La Fontaine,” antonomasia between common and proper noun, evoking the name of the author of many fables in the common “fountain,” itself a euphemistic title for a urinal. Ulmer’s collage of the urinal with a cover of La Fontaine’s book make the joke explicit. Duchamp’s commitment to the punning bachelor machine logic central to modernism is well known. He acknowledged his attendance at a performance of a stage adaptation of Raymond Roussel’s 1910 novel Impressions of Africa as a turning point in his career (Roussel’s method of composition used generative puns). It has been suggested that some of the Readymades at least are comments on dreams described in Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, hence that they use rebus methods (visualizations evoking words). Freud noted, for example, that many dreams are triggered when sleepers experience the need to urinate (the dream allows sleep to continue briefly). The text of the fabled fountain is provided by its history, being as it is the most influential (if not the “best”) art work of the twentieth century, including its status as a prank, and all the manipulations Duchamp performed to put the image of La Fontaine into circulation, recorded in Thierry De Duve’s Kant After Duchamp. What is the moral of the readymade fable? –Martin Kippenberger, “Rameau’s Nephew,” 1988

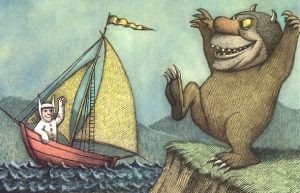

–Martin Kippenberger, “Rameau’s Nephew,” 1988 Maurice Sendak is best known for his Caldecott Medal winning illustrated children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963), made into

Maurice Sendak is best known for his Caldecott Medal winning illustrated children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963), made into  –Family (Personal): Composition of mystory usually begins with a memory from early childhood, life with the family. Up to three such memories are allowed, to avoid getting stuck deciding on one that is most important (that dilemma if it arises is resolved when the remaining slots are filled, following the rule what resembles assembles). Sendak proposed two memories: the first was one of his earliest, an encounter with one of the pedagogical objects Pasolini mentioned, a book his older sister received from her book club. The book was very thick with a hardcover of pale green with gold lettering. Although not yet able to read, Sendak was fascinated with the book and demanded to have it, creating so much commotion the parents made his sister give it to him. When he finally returned it to his sister it was in bad shape, including suffering from being licked all over.

–Family (Personal): Composition of mystory usually begins with a memory from early childhood, life with the family. Up to three such memories are allowed, to avoid getting stuck deciding on one that is most important (that dilemma if it arises is resolved when the remaining slots are filled, following the rule what resembles assembles). Sendak proposed two memories: the first was one of his earliest, an encounter with one of the pedagogical objects Pasolini mentioned, a book his older sister received from her book club. The book was very thick with a hardcover of pale green with gold lettering. Although not yet able to read, Sendak was fascinated with the book and demanded to have it, creating so much commotion the parents made his sister give it to him. When he finally returned it to his sister it was in bad shape, including suffering from being licked all over. I was eleven when I saw the movie, and I remember it vividly because of how intensely in frightened me. The moment I am talking about is the one when Dorothy is trapped by the Wicked Witch of the West, and the witch takes an hourglass and turns it over and says something horrible like, “When the sand runs out, you’re dead, honey.” Judy Garland is left alone in the room, and one of her best moments ever was her way of saying, “I’m frightened,” and then, as though that realization has just actually dawned on her, says it a second time, “I’m frightened.” I still remember how her hand went to her head–the way she had of fluttering her hand, her desperation was so convincing. There was no way out of that room, nothing she could do. And suddenly, in the witch’s crystal ball, she sees her Auntie Em, back in Kansas, standing in the yard and calling to her. And she rushes to the crystal ball, and stands over it and screams, “Auntie Em! Here I am!”

I was eleven when I saw the movie, and I remember it vividly because of how intensely in frightened me. The moment I am talking about is the one when Dorothy is trapped by the Wicked Witch of the West, and the witch takes an hourglass and turns it over and says something horrible like, “When the sand runs out, you’re dead, honey.” Judy Garland is left alone in the room, and one of her best moments ever was her way of saying, “I’m frightened,” and then, as though that realization has just actually dawned on her, says it a second time, “I’m frightened.” I still remember how her hand went to her head–the way she had of fluttering her hand, her desperation was so convincing. There was no way out of that room, nothing she could do. And suddenly, in the witch’s crystal ball, she sees her Auntie Em, back in Kansas, standing in the yard and calling to her. And she rushes to the crystal ball, and stands over it and screams, “Auntie Em! Here I am!” The major event of my childhood was the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932. That nightmare was probably the origin of my conviction that children can’t be shielded from frightening truths. Although I was only three, I remember intensely the details of the Lindbergh case. Lindbergh was our Prince Charles, and his wife was our Princess Di. I particularly remember a newspaper that had the front-page headline LINDBERGH BABY FOUND DEAD and a photograph of a scene in the woods with a black arrow pointing to something awful. I’ve since learned that Colonel Lindbergh threatened to sue if the New York Daily News didn’t have the morning edition pulled off the newsstands, so I guess not many people saw the picture. But I saw the picture.

The major event of my childhood was the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932. That nightmare was probably the origin of my conviction that children can’t be shielded from frightening truths. Although I was only three, I remember intensely the details of the Lindbergh case. Lindbergh was our Prince Charles, and his wife was our Princess Di. I particularly remember a newspaper that had the front-page headline LINDBERGH BABY FOUND DEAD and a photograph of a scene in the woods with a black arrow pointing to something awful. I’ve since learned that Colonel Lindbergh threatened to sue if the New York Daily News didn’t have the morning edition pulled off the newsstands, so I guess not many people saw the picture. But I saw the picture.

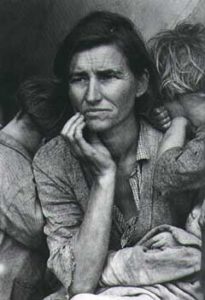

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times.

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times. This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”

This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”

Situation.What does it mean to approach Everyday Life with an aesthetic attitude? There is nothing novel about framing one’s quotidian roles in some state of mind — wisdom, science, religion. As practice, the aesthetic attitude is included within a situation, adding to the intentionality of some project the distance that generates aura of signification. “Situation” is a guideword, evoking the existentialist point that circumstances become a situation when considered from the point of view of one’s “project,” the goals of a practice, encountering a scene not indifferently but according to its affordances for some purpose. In a Visit (for konsult) this project or purpose is given an aesthetic frame.

Situation.What does it mean to approach Everyday Life with an aesthetic attitude? There is nothing novel about framing one’s quotidian roles in some state of mind — wisdom, science, religion. As practice, the aesthetic attitude is included within a situation, adding to the intentionality of some project the distance that generates aura of signification. “Situation” is a guideword, evoking the existentialist point that circumstances become a situation when considered from the point of view of one’s “project,” the goals of a practice, encountering a scene not indifferently but according to its affordances for some purpose. In a Visit (for konsult) this project or purpose is given an aesthetic frame. The function of heuretics is to create a discourse on method: The method you need has to be generated even while you are applying it. Blogs are a good support for this generative practice, since they enable a developmental unfolding. A project experiment is set (the design of konsult for EmerAgency catalysis of public policy dilemmas), a set of resources are chosen as generators, assigned to slots in the CATTt, and each resource is inventoried in turn, in a sequence from which emerges an intertext, to be synthesized and integrated into a working recipe. Blogs document this process, inventorying each resource as it is encountered, itemizing instructions from the operating features of the resource, testing them in part, while moving through the sequence, integrating instructions for further testing. The result is both a commentary on and demonstration of the desired poetics.

The function of heuretics is to create a discourse on method: The method you need has to be generated even while you are applying it. Blogs are a good support for this generative practice, since they enable a developmental unfolding. A project experiment is set (the design of konsult for EmerAgency catalysis of public policy dilemmas), a set of resources are chosen as generators, assigned to slots in the CATTt, and each resource is inventoried in turn, in a sequence from which emerges an intertext, to be synthesized and integrated into a working recipe. Blogs document this process, inventorying each resource as it is encountered, itemizing instructions from the operating features of the resource, testing them in part, while moving through the sequence, integrating instructions for further testing. The result is both a commentary on and demonstration of the desired poetics.

The further step of using the CATTt is to extrapolate from these operating features, to adopt them as forms only, substituting one’s own materials suggested by the relay, to test an allegory of prudence (aesthetic judgment) drawing on equivalents of the features found in the source Theory.

The further step of using the CATTt is to extrapolate from these operating features, to adopt them as forms only, substituting one’s own materials suggested by the relay, to test an allegory of prudence (aesthetic judgment) drawing on equivalents of the features found in the source Theory.