Primal Scene: Curriculum

Mystory Curriculum. Mystory may be hermeneutic as well as heuretic, that is, it may be used to organize the curriculum, as part of a transition from literacy to electracy. It is persuasive in any case to find the image of wide scope as a structural principle operating in the arts. Examples of works across media manifesting wide images are assigned in a DH curriculum as exemplars and relays guiding egents in the design of their own wide images.

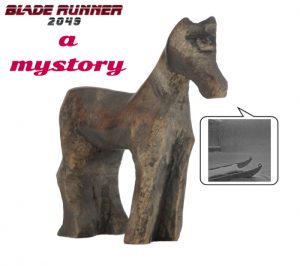

–Blade Runner 2049. A recent example is the Blade Runner sequel, the organizing role played by childhood memories in simulating human identity for replicants. The sequel narrative is motivated by the protagonist’s investigation of the memory of a carved wooden horse. This motif alludes formally and intertextually to the Orson Welles film, Citizen Kane-– the simulated documentary investigation into the enigma of Kane’s identity, his deathbed statement, “Rosebud.” The audience learns that “Rosebud” is the name of Kane’s sled, metonym of his childhood happiness. A konsult curriculum studies these works at several levels, to understand the relationship of lived experience to formal design.

–Blade Runner 2049. A recent example is the Blade Runner sequel, the organizing role played by childhood memories in simulating human identity for replicants. The sequel narrative is motivated by the protagonist’s investigation of the memory of a carved wooden horse. This motif alludes formally and intertextually to the Orson Welles film, Citizen Kane-– the simulated documentary investigation into the enigma of Kane’s identity, his deathbed statement, “Rosebud.” The audience learns that “Rosebud” is the name of Kane’s sled, metonym of his childhood happiness. A konsult curriculum studies these works at several levels, to understand the relationship of lived experience to formal design.

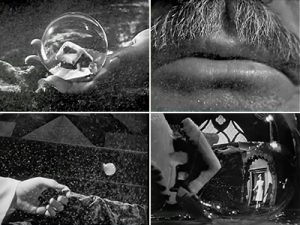

–Intertext. The seminar reads or screens the works mentioned here, analyzing how early memories function in both formal and thematic terms. Citizen Kane, often cited as the best American film ever made, is structured around a journalist’s attempt to solve the mystery of the dying Kane’s last word, “Rosebud.” The audience learns in the final scene that “Rosebud” is the name of Kane’s childhood sled, emblematic of his moment of happiness, in the genre of Proust’s madeleine, whose taste triggered a recollection of happiness whose source it was the goal of the novel to discover. The carved horse, the sled, are vehicles whose tenor the fictional works dramatize, to form hypothetical wide images.

–Murakami. Another example is 1Q84, by Haruki Murakami, one of whose characters (Tengo) is driven by an early childhood memory. “Murakami’s other protagonist, a writer and math tutor named Tengo, begins 1Q84 in something of an epileptic fit. These attacks strike regularly, we learn (and come to witness), triggered by the bubbling up to consciousness of Tengo’s first memory, witnessed from the crib: ‘His mother had taken off her blouse and dropped the shoulder strap of her white slip to let a man who was not his father suck on her breasts.’ Duly unrepressed, the memory paralyzes his limbs, cuts off his breathing, and occasions the novel’s single most eyebrow-raising sentence: ‘The tsunami’s liquid wall swallowed him whole.'”

–Murakami. Another example is 1Q84, by Haruki Murakami, one of whose characters (Tengo) is driven by an early childhood memory. “Murakami’s other protagonist, a writer and math tutor named Tengo, begins 1Q84 in something of an epileptic fit. These attacks strike regularly, we learn (and come to witness), triggered by the bubbling up to consciousness of Tengo’s first memory, witnessed from the crib: ‘His mother had taken off her blouse and dropped the shoulder strap of her white slip to let a man who was not his father suck on her breasts.’ Duly unrepressed, the memory paralyzes his limbs, cuts off his breathing, and occasions the novel’s single most eyebrow-raising sentence: ‘The tsunami’s liquid wall swallowed him whole.'”

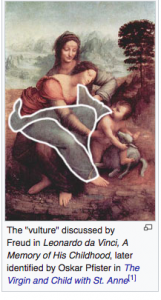

–Leonardo da Vinci. Sigmund Freud’s biographical study of Leonardo featured the one early memory Leonardo recorded in his journals. “It seems that it had been destined before that I should occupy myself so thoroughly with the vulture, for it comes to my mind as a very early memory, when I was still in the cradle, a vulture came down to me, he opened my mouth with his tail and struck me a few times with his tail against my lips.” We will return to these examples later. The point for now is just to note childhood early memories as an important motif in literature, cinema, philosophy, as resource for our heuretic curriculum. Such works are assigned, discussed, interpreted, for their own sake, but also as relays, poetics for design of egent wide images.

–Leonardo da Vinci. Sigmund Freud’s biographical study of Leonardo featured the one early memory Leonardo recorded in his journals. “It seems that it had been destined before that I should occupy myself so thoroughly with the vulture, for it comes to my mind as a very early memory, when I was still in the cradle, a vulture came down to me, he opened my mouth with his tail and struck me a few times with his tail against my lips.” We will return to these examples later. The point for now is just to note childhood early memories as an important motif in literature, cinema, philosophy, as resource for our heuretic curriculum. Such works are assigned, discussed, interpreted, for their own sake, but also as relays, poetics for design of egent wide images.

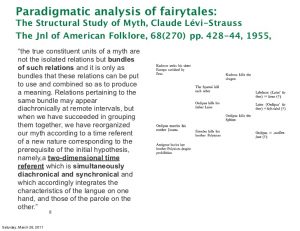

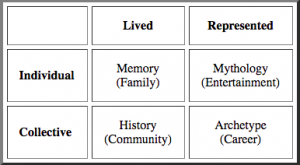

Structuralism: Claude Lévi-Strauss. Following the rule of heuretics curriculum, to treat one’s own materials as belonging to the disciplinary tradition, I applied Lévi-Strauss’s insights into the formal design of mythologies to my wide image. The wide mage in fact is a personal mythology, not only metaphorically but formally. Lévi-Strauss showed that individual instances of a myth manifest a system of relationships, covering all possible variations on the aporia (disaster in our terms) addressed by the myth. The system of relationships is that of proportional analogy (A is to B as C is to D), the figure of hypotyposis encountered throughout the tradition. The practice of myth-work applied to a mystory set (including the Career register documented, along with Family, Entertainment, Community) is to determine which stories/scenes are related in this proportional ratio, along what axes? In my case I found Family and Career related on an axis of space (The Sand and Gravel Plant scene, materializing the Choral metaphor of Plato and Derrida); Entertainment and History related on an axis of time. High Noon plays out almost in real time, intercutting between the clock in the sheriff’s office and the gunmen waiting for their boss to arrive on the noon train, while the sheriff tries to form a posse to fight them. Custer took his Seventh Cavalry far ahead of the rest of the advancing army, hoping to strike a quick blow against the Indians, to get the glory for himself, to propel him into candidacy for President of the United States in the 1876 election.. The symmetries formed in the crossings of this four-fold are provocative, suggestive of a diagram capable of translation into an original hypothesis for konsult.

Structuralism: Claude Lévi-Strauss. Following the rule of heuretics curriculum, to treat one’s own materials as belonging to the disciplinary tradition, I applied Lévi-Strauss’s insights into the formal design of mythologies to my wide image. The wide mage in fact is a personal mythology, not only metaphorically but formally. Lévi-Strauss showed that individual instances of a myth manifest a system of relationships, covering all possible variations on the aporia (disaster in our terms) addressed by the myth. The system of relationships is that of proportional analogy (A is to B as C is to D), the figure of hypotyposis encountered throughout the tradition. The practice of myth-work applied to a mystory set (including the Career register documented, along with Family, Entertainment, Community) is to determine which stories/scenes are related in this proportional ratio, along what axes? In my case I found Family and Career related on an axis of space (The Sand and Gravel Plant scene, materializing the Choral metaphor of Plato and Derrida); Entertainment and History related on an axis of time. High Noon plays out almost in real time, intercutting between the clock in the sheriff’s office and the gunmen waiting for their boss to arrive on the noon train, while the sheriff tries to form a posse to fight them. Custer took his Seventh Cavalry far ahead of the rest of the advancing army, hoping to strike a quick blow against the Indians, to get the glory for himself, to propel him into candidacy for President of the United States in the 1876 election.. The symmetries formed in the crossings of this four-fold are provocative, suggestive of a diagram capable of translation into an original hypothesis for konsult.

Wide Image into Diagram. The next step after using the emblem catechism to generate wide image is to begin translation into diagrams, extracting patterns from the intervals and relationships emerging within the matrix. Composing my first mystory in the mid-1980s, “Derrida at the Little Bighorn,” I discovered a match between Family and Career that produced an epiphany I have developed ever since. One of my first jobs when I worked at the plant was to clean the grids of the screens used to grade the gravel into sizes. Eventually the screens plugged up with stones and I had to knock them loose with a hammer. The pea-gravel screen could be cleaned by running the tip of a large screwdriver along the meshed grids, which produced an almost musical sound. This was the actual “gravel plant.” The washer with its three grades of screen, one on top of the other, was fed by a conveyor belt carrying the pit gravel from the quarry, and fed in turn three piles of sized rock, with the sand coming out the bottom. The whole contraption made a terrible noise and shook violently. I realized years later, reading Plato’s Timaeus after Derrida, that this gravel washer was a good metaphor or model for the operation of chora, sorting chaos into Earth, Air, Fire, Water.

Wide Image into Diagram. The next step after using the emblem catechism to generate wide image is to begin translation into diagrams, extracting patterns from the intervals and relationships emerging within the matrix. Composing my first mystory in the mid-1980s, “Derrida at the Little Bighorn,” I discovered a match between Family and Career that produced an epiphany I have developed ever since. One of my first jobs when I worked at the plant was to clean the grids of the screens used to grade the gravel into sizes. Eventually the screens plugged up with stones and I had to knock them loose with a hammer. The pea-gravel screen could be cleaned by running the tip of a large screwdriver along the meshed grids, which produced an almost musical sound. This was the actual “gravel plant.” The washer with its three grades of screen, one on top of the other, was fed by a conveyor belt carrying the pit gravel from the quarry, and fed in turn three piles of sized rock, with the sand coming out the bottom. The whole contraption made a terrible noise and shook violently. I realized years later, reading Plato’s Timaeus after Derrida, that this gravel washer was a good metaphor or model for the operation of chora, sorting chaos into Earth, Air, Fire, Water. –Derrida, Chora-L As part of his collaboration with the architect, Peter Eisenman, on a design for one of the folies, to be included in the Park for Creativity, Parc de la Villette, in Paris, Derrida produced a drawing and a descriptive concept for an impossible project: to build Chora. “I propose therefore the following ‘materialisation’: in one or three exemplars (with different scalings) a gilded metallic object will be planted obliquely in the ground. Neither vertical nor horizontal, a most solid frame will resemble at once a mesh, sieve, or grid and a stringed musical instrument. An interpretive and selective filter which will have permitted a reading and sifting of the three sites [at the Park] and the three embeddings.”

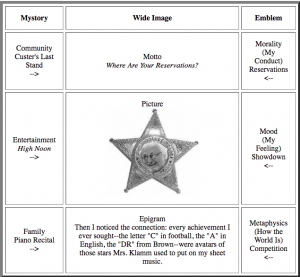

–Derrida, Chora-L As part of his collaboration with the architect, Peter Eisenman, on a design for one of the folies, to be included in the Park for Creativity, Parc de la Villette, in Paris, Derrida produced a drawing and a descriptive concept for an impossible project: to build Chora. “I propose therefore the following ‘materialisation’: in one or three exemplars (with different scalings) a gilded metallic object will be planted obliquely in the ground. Neither vertical nor horizontal, a most solid frame will resemble at once a mesh, sieve, or grid and a stringed musical instrument. An interpretive and selective filter which will have permitted a reading and sifting of the three sites [at the Park] and the three embeddings.” –Tenor (Themata): Catechism. The image on the left is the emblem Ulmer generated from his mystory, leading to design of his wide image in

–Tenor (Themata): Catechism. The image on the left is the emblem Ulmer generated from his mystory, leading to design of his wide image in  3) The third question is Mood: given the necessity to act in that way, in a world of that character, how do I feel? Wabi-Sabi advises acceptance of the inevitable and appreciation of the cosmic order. Ulmer found his state of mind expressed in High Noon as a fable of duty: despite his contempt for the hypocritical community, the sheriff fought the gang of killers, after which he threw away the tin star. This gesture of discarding the badge of status determined the tin star as the icon of the emblem. In practice it is best to decide which popcycle story supplies the picture, and which question of the catechism that story answers, and the rest of the emblem follows from there.

3) The third question is Mood: given the necessity to act in that way, in a world of that character, how do I feel? Wabi-Sabi advises acceptance of the inevitable and appreciation of the cosmic order. Ulmer found his state of mind expressed in High Noon as a fable of duty: despite his contempt for the hypocritical community, the sheriff fought the gang of killers, after which he threw away the tin star. This gesture of discarding the badge of status determined the tin star as the icon of the emblem. In practice it is best to decide which popcycle story supplies the picture, and which question of the catechism that story answers, and the rest of the emblem follows from there. The Way to Rainy Mountain. Son of a White mother and Kiowa father, Momaday was raised on a reservation. His novel House Made of Dawn won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969. His autobiographical The Way to Rainy Mountain was assigned as relay modeling the micro form and overall structuring by means of signifiers repeating across levels of the popcycle. Rainy Mountain juxtaposes Kiowa myths Momaday learned from his grandmother; the actual history of the Kiowa symbolized in the myths; his personal recollections of his childhood on the reservation. The text manifests identification (with his grandmother Aho and his grandfather Mammedaty); the use of pattern (the unity of each section is created by the repetition of a detail within the exposition across the three discourses); the use of setting to express feeling (the memories of scenes from the reservation). Most important is the location of Momaday’s memories of childhood in the context of the traditional stories and actual history of his Community (Kiowa), thus bringing the three levels of his symbolic experience into contact–personal, historical, mythical (entertainment fictions in a modern point of view). The book is a collection of thirty-four three-paragraph units (plus introduction and epilogue) illustrated with drawings by Momaday’s father. Unit 3 is cited as example: the popcycle sequence is always the same: Mythology; History; Memory.

The Way to Rainy Mountain. Son of a White mother and Kiowa father, Momaday was raised on a reservation. His novel House Made of Dawn won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969. His autobiographical The Way to Rainy Mountain was assigned as relay modeling the micro form and overall structuring by means of signifiers repeating across levels of the popcycle. Rainy Mountain juxtaposes Kiowa myths Momaday learned from his grandmother; the actual history of the Kiowa symbolized in the myths; his personal recollections of his childhood on the reservation. The text manifests identification (with his grandmother Aho and his grandfather Mammedaty); the use of pattern (the unity of each section is created by the repetition of a detail within the exposition across the three discourses); the use of setting to express feeling (the memories of scenes from the reservation). Most important is the location of Momaday’s memories of childhood in the context of the traditional stories and actual history of his Community (Kiowa), thus bringing the three levels of his symbolic experience into contact–personal, historical, mythical (entertainment fictions in a modern point of view). The book is a collection of thirty-four three-paragraph units (plus introduction and epilogue) illustrated with drawings by Momaday’s father. Unit 3 is cited as example: the popcycle sequence is always the same: Mythology; History; Memory. III

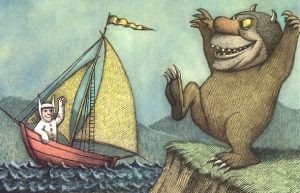

III Maurice Sendak is best known for his Caldecott Medal winning illustrated children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963), made into

Maurice Sendak is best known for his Caldecott Medal winning illustrated children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963), made into  –Family (Personal): Composition of mystory usually begins with a memory from early childhood, life with the family. Up to three such memories are allowed, to avoid getting stuck deciding on one that is most important (that dilemma if it arises is resolved when the remaining slots are filled, following the rule what resembles assembles). Sendak proposed two memories: the first was one of his earliest, an encounter with one of the pedagogical objects Pasolini mentioned, a book his older sister received from her book club. The book was very thick with a hardcover of pale green with gold lettering. Although not yet able to read, Sendak was fascinated with the book and demanded to have it, creating so much commotion the parents made his sister give it to him. When he finally returned it to his sister it was in bad shape, including suffering from being licked all over.

–Family (Personal): Composition of mystory usually begins with a memory from early childhood, life with the family. Up to three such memories are allowed, to avoid getting stuck deciding on one that is most important (that dilemma if it arises is resolved when the remaining slots are filled, following the rule what resembles assembles). Sendak proposed two memories: the first was one of his earliest, an encounter with one of the pedagogical objects Pasolini mentioned, a book his older sister received from her book club. The book was very thick with a hardcover of pale green with gold lettering. Although not yet able to read, Sendak was fascinated with the book and demanded to have it, creating so much commotion the parents made his sister give it to him. When he finally returned it to his sister it was in bad shape, including suffering from being licked all over. I was eleven when I saw the movie, and I remember it vividly because of how intensely in frightened me. The moment I am talking about is the one when Dorothy is trapped by the Wicked Witch of the West, and the witch takes an hourglass and turns it over and says something horrible like, “When the sand runs out, you’re dead, honey.” Judy Garland is left alone in the room, and one of her best moments ever was her way of saying, “I’m frightened,” and then, as though that realization has just actually dawned on her, says it a second time, “I’m frightened.” I still remember how her hand went to her head–the way she had of fluttering her hand, her desperation was so convincing. There was no way out of that room, nothing she could do. And suddenly, in the witch’s crystal ball, she sees her Auntie Em, back in Kansas, standing in the yard and calling to her. And she rushes to the crystal ball, and stands over it and screams, “Auntie Em! Here I am!”

I was eleven when I saw the movie, and I remember it vividly because of how intensely in frightened me. The moment I am talking about is the one when Dorothy is trapped by the Wicked Witch of the West, and the witch takes an hourglass and turns it over and says something horrible like, “When the sand runs out, you’re dead, honey.” Judy Garland is left alone in the room, and one of her best moments ever was her way of saying, “I’m frightened,” and then, as though that realization has just actually dawned on her, says it a second time, “I’m frightened.” I still remember how her hand went to her head–the way she had of fluttering her hand, her desperation was so convincing. There was no way out of that room, nothing she could do. And suddenly, in the witch’s crystal ball, she sees her Auntie Em, back in Kansas, standing in the yard and calling to her. And she rushes to the crystal ball, and stands over it and screams, “Auntie Em! Here I am!” The major event of my childhood was the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932. That nightmare was probably the origin of my conviction that children can’t be shielded from frightening truths. Although I was only three, I remember intensely the details of the Lindbergh case. Lindbergh was our Prince Charles, and his wife was our Princess Di. I particularly remember a newspaper that had the front-page headline LINDBERGH BABY FOUND DEAD and a photograph of a scene in the woods with a black arrow pointing to something awful. I’ve since learned that Colonel Lindbergh threatened to sue if the New York Daily News didn’t have the morning edition pulled off the newsstands, so I guess not many people saw the picture. But I saw the picture.

The major event of my childhood was the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932. That nightmare was probably the origin of my conviction that children can’t be shielded from frightening truths. Although I was only three, I remember intensely the details of the Lindbergh case. Lindbergh was our Prince Charles, and his wife was our Princess Di. I particularly remember a newspaper that had the front-page headline LINDBERGH BABY FOUND DEAD and a photograph of a scene in the woods with a black arrow pointing to something awful. I’ve since learned that Colonel Lindbergh threatened to sue if the New York Daily News didn’t have the morning edition pulled off the newsstands, so I guess not many people saw the picture. But I saw the picture. Our first memories are visual ones. In memory life becomes a silent film. We all have in our minds an image which is the first, or one of the first, in our lives. That image is a sign, or to be exact, a linguistic sign. So if it is a linguistic sign it communicates or expresses something. I shall give you an example. The first image of my life is a white, transparent bind, which hangs–without moving, I believe–from a window which looks out on to a somewhat sad and dark lane. That blind terrifies me and fills me with anguish: not as something threatening and unpleasant but as something cosmic. In that blind the spirit of the middle-class house in Bologna where I was born is summed up and takes bodily form. Indeed the images which compete with the blind for chronological primacy are a room with an alcove (where my grandmother slept), heavy “proper” furniture, a carriage in the street which I wanted to climb into. These images are less painful than that of the blind, yet in them too there is concentrated that element of the cosmic which constitutes the petty bourgeois spirit of the world into which I was born. But if in the objects and things the images which have remained firmly in my memory (like those of an indelible dream) there is precipitated and concentrated the whole world of “memories,” which is recalled by those images in a single instant– if, that is to say, those object and those things are containers in which is stored a universe which I can extract and look at, then, at the same time, these objects and things are also something other than a container. . . . So their communication was essentially instructional. They taught me where I had been born, in what world I lived, and above all how to think about my birth and my life. Since it was a question of an unarticulated, fixed and incontrovertible pedagogic discourse, it could not be other–as we say today–than authoritarian and repressive. What that blind said to me and taught me did not admit (and does not admit) of rejoinders. No dialogue was possible or admissible with it, nor any act of self-education. That is why I believed that the whole world was the world which that blind taught me: that is to say, I thought that the whole world was “proper,” idealistic, sad and skeptical, a little vulgar–in short, petty bourgeois. (Pier Paolo Pasolini, Lutheran Letters, trans. Stuart Hood. Carcanet Press: New York, 1987).

Our first memories are visual ones. In memory life becomes a silent film. We all have in our minds an image which is the first, or one of the first, in our lives. That image is a sign, or to be exact, a linguistic sign. So if it is a linguistic sign it communicates or expresses something. I shall give you an example. The first image of my life is a white, transparent bind, which hangs–without moving, I believe–from a window which looks out on to a somewhat sad and dark lane. That blind terrifies me and fills me with anguish: not as something threatening and unpleasant but as something cosmic. In that blind the spirit of the middle-class house in Bologna where I was born is summed up and takes bodily form. Indeed the images which compete with the blind for chronological primacy are a room with an alcove (where my grandmother slept), heavy “proper” furniture, a carriage in the street which I wanted to climb into. These images are less painful than that of the blind, yet in them too there is concentrated that element of the cosmic which constitutes the petty bourgeois spirit of the world into which I was born. But if in the objects and things the images which have remained firmly in my memory (like those of an indelible dream) there is precipitated and concentrated the whole world of “memories,” which is recalled by those images in a single instant– if, that is to say, those object and those things are containers in which is stored a universe which I can extract and look at, then, at the same time, these objects and things are also something other than a container. . . . So their communication was essentially instructional. They taught me where I had been born, in what world I lived, and above all how to think about my birth and my life. Since it was a question of an unarticulated, fixed and incontrovertible pedagogic discourse, it could not be other–as we say today–than authoritarian and repressive. What that blind said to me and taught me did not admit (and does not admit) of rejoinders. No dialogue was possible or admissible with it, nor any act of self-education. That is why I believed that the whole world was the world which that blind taught me: that is to say, I thought that the whole world was “proper,” idealistic, sad and skeptical, a little vulgar–in short, petty bourgeois. (Pier Paolo Pasolini, Lutheran Letters, trans. Stuart Hood. Carcanet Press: New York, 1987).

When it comes to the image of wide scope (four or five fundamental images structuring imagination, and central to the history of invention), the prototype is Einstein’s compass (received from his father as a gift at age four or five): the wide image is a compass for the existential positioning system of learning, to orient egents tracking the vector of invention.

When it comes to the image of wide scope (four or five fundamental images structuring imagination, and central to the history of invention), the prototype is Einstein’s compass (received from his father as a gift at age four or five): the wide image is a compass for the existential positioning system of learning, to orient egents tracking the vector of invention. Here is Existential Positioning (EPS) in experience. How common is it to have an intuition of mortality during childhood? It is as if each person has to realize for him/herself individually what the sages codified in Ancient philosophy as ataraxy. Ataraxy is a state of mind in which the sage, realizing that s/he has no control over external events, decides to reduce her/his own desires. This ascetic view is associated with the stance that “philosophy is learning how to die.” Paradoxically, it may seem, philosophers insist that the realization that everyone dies is liberating. Since death is inevitable, why get so excited over one’s successes and failures in life? Of course, various response to this intuition are possible, such as carpe diem (seize the day).

Here is Existential Positioning (EPS) in experience. How common is it to have an intuition of mortality during childhood? It is as if each person has to realize for him/herself individually what the sages codified in Ancient philosophy as ataraxy. Ataraxy is a state of mind in which the sage, realizing that s/he has no control over external events, decides to reduce her/his own desires. This ascetic view is associated with the stance that “philosophy is learning how to die.” Paradoxically, it may seem, philosophers insist that the realization that everyone dies is liberating. Since death is inevitable, why get so excited over one’s successes and failures in life? Of course, various response to this intuition are possible, such as carpe diem (seize the day). A primal scene? The boy is eleven, starting seventh grade. His father explains that it is time to learn the value of work. He has arranged a job for his son with a friend whose name is Cutting and who owns a sheet metal shop. Every Saturday the boy rides his bicycle across town to Cutting’s Sheet Metal. The employees are done for the week at noon on Saturday. He has to arrive by noon so the boss can lock up, leaving the boy inside (he is too young to be trusted with a key). The job is to clean the shop — sweep the floor, gather up the tools and align them neatly in their designated places on the work benches, collect the remnants and clippings of the metal sheets scattered everywhere. It takes most of the afternoon to finish the chores. The shop is a cavernous open warehouse, with rows of heavy tables, the walls lined with shelves stacked to the distant ceiling with equipment, tools, metals. It is quiet, the stillness of dust motes swirling in the beams of sunlight filtered through the few windows high up near the roof, carving vectors through deep shadow. The sunlight catches the edges of a museum of blades, a taxonomy of every snipping snap slice chop saw hack rend rip cleave nip or severing machine. Half-shaped tin objects stand in rows behind piles of hammers and modelling frames. After so many weeks and months of Saturday noons the boy begins to lose touch with his former friends and companions, who go their separate ways.

A primal scene? The boy is eleven, starting seventh grade. His father explains that it is time to learn the value of work. He has arranged a job for his son with a friend whose name is Cutting and who owns a sheet metal shop. Every Saturday the boy rides his bicycle across town to Cutting’s Sheet Metal. The employees are done for the week at noon on Saturday. He has to arrive by noon so the boss can lock up, leaving the boy inside (he is too young to be trusted with a key). The job is to clean the shop — sweep the floor, gather up the tools and align them neatly in their designated places on the work benches, collect the remnants and clippings of the metal sheets scattered everywhere. It takes most of the afternoon to finish the chores. The shop is a cavernous open warehouse, with rows of heavy tables, the walls lined with shelves stacked to the distant ceiling with equipment, tools, metals. It is quiet, the stillness of dust motes swirling in the beams of sunlight filtered through the few windows high up near the roof, carving vectors through deep shadow. The sunlight catches the edges of a museum of blades, a taxonomy of every snipping snap slice chop saw hack rend rip cleave nip or severing machine. Half-shaped tin objects stand in rows behind piles of hammers and modelling frames. After so many weeks and months of Saturday noons the boy begins to lose touch with his former friends and companions, who go their separate ways. What happens then? The light and shadow of the industrial building open all at once onto a void, a black hole and white wall of divided worlds in this little infinite town: the official world of adults (parents, teachers, coaches, ministers, scout masters) that until then had constituted reality, and the unofficial world of his peers, whose existence he had only just discovered. Two completely different systems of virtue and vice, success and failure, winning and losing, visibility and invisibility, were enforced in these realms: systems Not only different, but opposite and in conflict. What earned admiration and respect in one was inversely judged in the other. He could not have articulated the revelation so abstractly then. The unexpected aspect of this scene is the sense of abandonment, solitary isolation, that overcomes the child, a spilling out or abjection, an absolute exhaling of substance, followed soon after by the inhaled relief of knowing that it doesn’t matter, since everyone and everything dies everywhere the same death.

What happens then? The light and shadow of the industrial building open all at once onto a void, a black hole and white wall of divided worlds in this little infinite town: the official world of adults (parents, teachers, coaches, ministers, scout masters) that until then had constituted reality, and the unofficial world of his peers, whose existence he had only just discovered. Two completely different systems of virtue and vice, success and failure, winning and losing, visibility and invisibility, were enforced in these realms: systems Not only different, but opposite and in conflict. What earned admiration and respect in one was inversely judged in the other. He could not have articulated the revelation so abstractly then. The unexpected aspect of this scene is the sense of abandonment, solitary isolation, that overcomes the child, a spilling out or abjection, an absolute exhaling of substance, followed soon after by the inhaled relief of knowing that it doesn’t matter, since everyone and everything dies everywhere the same death.