Gest 3 (Family)

Family gesture: Nancy Kitchel provides a relay for how to locate mood or atmosphere in a local and family setting.

“Covering My Face: My Grandmother’s Gestures,” 1973

How a particular Midwestern storytelling tradition resembles the landscape. How my aunt or my mother can tell a story in such a way that the peaks (of violence) are cut off and the low points are filled up (with details, with emphasis), until the whole is perfectly flat and contains the violence.

This family gesture may be linked with the iconic gestures found in religious art and contemporary entertainment media.

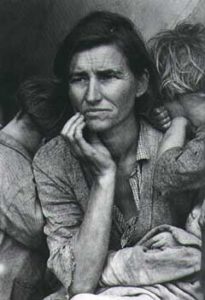

Gestures and Icons. Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, Dorothea Lange, 1936

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times.

Nancy Kitchel’s “grandmother’s gesture” may be seen as a series of variations on a gesture of worry and anxiety codified in this photograph taken by Dorothea Lange as part of a New Deal project to document the misery of migrant workers, sponsored by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is one of the most-cited pictorial images of our times.

A repetition of gestures of this sort opens a conductive inference path between (in this case) Family and History. If Kitchel were doing our assignment this gesture would justify a search in documentation of “the Great Depression” to find a metaphor to express the mood of her Family circumstances.

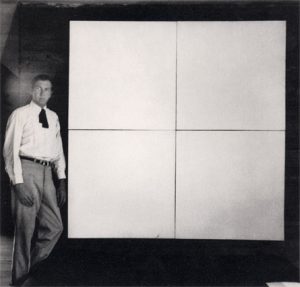

–Landscape Gest (Outer Scene = State of Mind). Kitchel provides another example of Existential Disaster (cosmic glimpse), inclulding visionary Whiteness.

“Last White (Interior Landscape)”, 1975

This idea I have that the whole inside of my head resembles this landscape (flat? nothing there?), that the particular, peculiar sense of great space, isolation in space, harshness, clarity, severity, the constant transitions, shifts, reveries, the wild swings form one state to another, forms the visual, auditory, reasoning, base for thought or action. A sense that I have been formed out of the quality of the landscape, that everything unnecessary is being slowly eroded by harsher elements. And the confidence that I will survive, denuded, or that something will survive, something will never stop.”

Nancy Wilson Kitchel, “Visible and Invisible” Individuals: Post-Movement Art in America

Ed. Alan Sondheim

But not yet have we solved the incantation of this whiteness, and learned why it appeals with such power to the soul; and more strange and far more portentous–why, as we have seen, it is at once the most meaning symbol of spiritual things, nay, the very veil of the Christian’s Deity; and yet should be as it is, the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind.

But not yet have we solved the incantation of this whiteness, and learned why it appeals with such power to the soul; and more strange and far more portentous–why, as we have seen, it is at once the most meaning symbol of spiritual things, nay, the very veil of the Christian’s Deity; and yet should be as it is, the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind. Our first memories are visual ones. In memory life becomes a silent film. We all have in our minds an image which is the first, or one of the first, in our lives. That image is a sign, or to be exact, a linguistic sign. So if it is a linguistic sign it communicates or expresses something. I shall give you an example. The first image of my life is a white, transparent bind, which hangs–without moving, I believe–from a window which looks out on to a somewhat sad and dark lane. That blind terrifies me and fills me with anguish: not as something threatening and unpleasant but as something cosmic. In that blind the spirit of the middle-class house in Bologna where I was born is summed up and takes bodily form. Indeed the images which compete with the blind for chronological primacy are a room with an alcove (where my grandmother slept), heavy “proper” furniture, a carriage in the street which I wanted to climb into. These images are less painful than that of the blind, yet in them too there is concentrated that element of the cosmic which constitutes the petty bourgeois spirit of the world into which I was born. But if in the objects and things the images which have remained firmly in my memory (like those of an indelible dream) there is precipitated and concentrated the whole world of “memories,” which is recalled by those images in a single instant– if, that is to say, those object and those things are containers in which is stored a universe which I can extract and look at, then, at the same time, these objects and things are also something other than a container. . . . So their communication was essentially instructional. They taught me where I had been born, in what world I lived, and above all how to think about my birth and my life. Since it was a question of an unarticulated, fixed and incontrovertible pedagogic discourse, it could not be other–as we say today–than authoritarian and repressive. What that blind said to me and taught me did not admit (and does not admit) of rejoinders. No dialogue was possible or admissible with it, nor any act of self-education. That is why I believed that the whole world was the world which that blind taught me: that is to say, I thought that the whole world was “proper,” idealistic, sad and skeptical, a little vulgar–in short, petty bourgeois. (Pier Paolo Pasolini, Lutheran Letters, trans. Stuart Hood. Carcanet Press: New York, 1987).

Our first memories are visual ones. In memory life becomes a silent film. We all have in our minds an image which is the first, or one of the first, in our lives. That image is a sign, or to be exact, a linguistic sign. So if it is a linguistic sign it communicates or expresses something. I shall give you an example. The first image of my life is a white, transparent bind, which hangs–without moving, I believe–from a window which looks out on to a somewhat sad and dark lane. That blind terrifies me and fills me with anguish: not as something threatening and unpleasant but as something cosmic. In that blind the spirit of the middle-class house in Bologna where I was born is summed up and takes bodily form. Indeed the images which compete with the blind for chronological primacy are a room with an alcove (where my grandmother slept), heavy “proper” furniture, a carriage in the street which I wanted to climb into. These images are less painful than that of the blind, yet in them too there is concentrated that element of the cosmic which constitutes the petty bourgeois spirit of the world into which I was born. But if in the objects and things the images which have remained firmly in my memory (like those of an indelible dream) there is precipitated and concentrated the whole world of “memories,” which is recalled by those images in a single instant– if, that is to say, those object and those things are containers in which is stored a universe which I can extract and look at, then, at the same time, these objects and things are also something other than a container. . . . So their communication was essentially instructional. They taught me where I had been born, in what world I lived, and above all how to think about my birth and my life. Since it was a question of an unarticulated, fixed and incontrovertible pedagogic discourse, it could not be other–as we say today–than authoritarian and repressive. What that blind said to me and taught me did not admit (and does not admit) of rejoinders. No dialogue was possible or admissible with it, nor any act of self-education. That is why I believed that the whole world was the world which that blind taught me: that is to say, I thought that the whole world was “proper,” idealistic, sad and skeptical, a little vulgar–in short, petty bourgeois. (Pier Paolo Pasolini, Lutheran Letters, trans. Stuart Hood. Carcanet Press: New York, 1987).