Tutorials & Guides

Terms: Popcycle

Popcycle. Learning is a complex adaptive system, and an aspect of what we are exploring is a certain isomorphism transversing all such systems. Heuretic pedagogy is describable within a systems perspective, beginning with the popcyle of institutions within which identity is constructed. Mystory (electrate equivalent of historiography) maps the position of a subject within the popcycle of institutions. The premise of heuretics is that there is an equivalent in learning of the four color theorem in mapping (choragraphy maps learning). “In mathematics, the four color theorem, or the four color map theorem, states that, given any separation of a plane into contiguous regions, producing a figure called a map, no more than four colors are required to color the regions of the map so that no two adjacent regions have the same color.” The analogy is that the four institutions of the popcycle suffice as interface relating a learner with every possible dimension of reality. This allusive argument is unpacked in subsequent posts, seeking further understanding, in configuring konsult as the mise-en-abyme of a popcycle.

Popcycle. Learning is a complex adaptive system, and an aspect of what we are exploring is a certain isomorphism transversing all such systems. Heuretic pedagogy is describable within a systems perspective, beginning with the popcyle of institutions within which identity is constructed. Mystory (electrate equivalent of historiography) maps the position of a subject within the popcycle of institutions. The premise of heuretics is that there is an equivalent in learning of the four color theorem in mapping (choragraphy maps learning). “In mathematics, the four color theorem, or the four color map theorem, states that, given any separation of a plane into contiguous regions, producing a figure called a map, no more than four colors are required to color the regions of the map so that no two adjacent regions have the same color.” The analogy is that the four institutions of the popcycle suffice as interface relating a learner with every possible dimension of reality. This allusive argument is unpacked in subsequent posts, seeking further understanding, in configuring konsult as the mise-en-abyme of a popcycle.

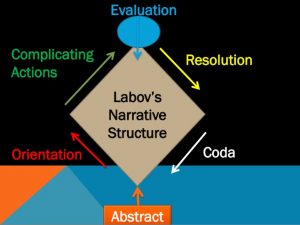

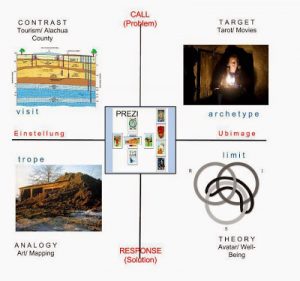

–Mandala. A basic diagram (popcycle mandala) is used consistently throughout KE to map and correlate correspondences across the layers and levels of the popcycle-mystory-wide image as Interface for the Stack of digital civilization. The diagram is not original, but is appropriated from various fourfold system templates. The diagram below registers the CATTt of a seminar documented in Ulmer’s blog, Routine, which includes extensive exposition of CATTt generators.

–Mandala. A basic diagram (popcycle mandala) is used consistently throughout KE to map and correlate correspondences across the layers and levels of the popcycle-mystory-wide image as Interface for the Stack of digital civilization. The diagram is not original, but is appropriated from various fourfold system templates. The diagram below registers the CATTt of a seminar documented in Ulmer’s blog, Routine, which includes extensive exposition of CATTt generators.

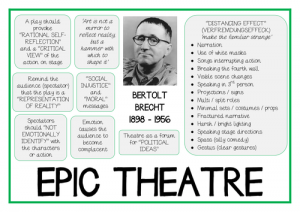

“Gest” is not supposed to mean gesticulation: it is not a matter of explana-tory or emphatic movements of the hands, but of overall attitudes. A language is gestic when it is grounded in a gest and conveys particular attitudes adopted by the speaker towards other men. The sentence “pluck the eye that offends thee out” is less effective from the gestic point of view than “if thine eve offend thee, pluck it out.” The latter starts by pre-senting the eye, and the first clause has the definite gest of making an assumption; the main clause then comes as a surprise, a piece of advice, and a relief.

“Gest” is not supposed to mean gesticulation: it is not a matter of explana-tory or emphatic movements of the hands, but of overall attitudes. A language is gestic when it is grounded in a gest and conveys particular attitudes adopted by the speaker towards other men. The sentence “pluck the eye that offends thee out” is less effective from the gestic point of view than “if thine eve offend thee, pluck it out.” The latter starts by pre-senting the eye, and the first clause has the definite gest of making an assumption; the main clause then comes as a surprise, a piece of advice, and a relief. Suppose that the musician composing a cantata on Lenin’s death has to reproduce his own attitude to the class struggle. As far as the gest goes, there are a number of different ways in which the report of Lenin’s death can be set. A certain dignity of presentation means little, since where death is involved this could also be held to be fitting in the case of an enemy. Anger at ‘the blind workings of providence’ cutting short the lives of the best members of the community would not be a communist gest; nor would a wise resignation to “life’s irony”; for the gest of communists mourning a communist is a very special one. The musician’s attitude to his text, the spokesman’s to his report, shows the extent of his political, and so of his human maturity. A man’s stature is shown by what he mourns and in what way he mourns it. To raise mourning to a high plane, to make it into an element of social progress: that is an artistic task.

Suppose that the musician composing a cantata on Lenin’s death has to reproduce his own attitude to the class struggle. As far as the gest goes, there are a number of different ways in which the report of Lenin’s death can be set. A certain dignity of presentation means little, since where death is involved this could also be held to be fitting in the case of an enemy. Anger at ‘the blind workings of providence’ cutting short the lives of the best members of the community would not be a communist gest; nor would a wise resignation to “life’s irony”; for the gest of communists mourning a communist is a very special one. The musician’s attitude to his text, the spokesman’s to his report, shows the extent of his political, and so of his human maturity. A man’s stature is shown by what he mourns and in what way he mourns it. To raise mourning to a high plane, to make it into an element of social progress: that is an artistic task. Here is Existential Positioning (EPS) in experience. How common is it to have an intuition of mortality during childhood? It is as if each person has to realize for him/herself individually what the sages codified in Ancient philosophy as ataraxy. Ataraxy is a state of mind in which the sage, realizing that s/he has no control over external events, decides to reduce her/his own desires. This ascetic view is associated with the stance that “philosophy is learning how to die.” Paradoxically, it may seem, philosophers insist that the realization that everyone dies is liberating. Since death is inevitable, why get so excited over one’s successes and failures in life? Of course, various response to this intuition are possible, such as carpe diem (seize the day).

Here is Existential Positioning (EPS) in experience. How common is it to have an intuition of mortality during childhood? It is as if each person has to realize for him/herself individually what the sages codified in Ancient philosophy as ataraxy. Ataraxy is a state of mind in which the sage, realizing that s/he has no control over external events, decides to reduce her/his own desires. This ascetic view is associated with the stance that “philosophy is learning how to die.” Paradoxically, it may seem, philosophers insist that the realization that everyone dies is liberating. Since death is inevitable, why get so excited over one’s successes and failures in life? Of course, various response to this intuition are possible, such as carpe diem (seize the day). A primal scene? The boy is eleven, starting seventh grade. His father explains that it is time to learn the value of work. He has arranged a job for his son with a friend whose name is Cutting and who owns a sheet metal shop. Every Saturday the boy rides his bicycle across town to Cutting’s Sheet Metal. The employees are done for the week at noon on Saturday. He has to arrive by noon so the boss can lock up, leaving the boy inside (he is too young to be trusted with a key). The job is to clean the shop — sweep the floor, gather up the tools and align them neatly in their designated places on the work benches, collect the remnants and clippings of the metal sheets scattered everywhere. It takes most of the afternoon to finish the chores. The shop is a cavernous open warehouse, with rows of heavy tables, the walls lined with shelves stacked to the distant ceiling with equipment, tools, metals. It is quiet, the stillness of dust motes swirling in the beams of sunlight filtered through the few windows high up near the roof, carving vectors through deep shadow. The sunlight catches the edges of a museum of blades, a taxonomy of every snipping snap slice chop saw hack rend rip cleave nip or severing machine. Half-shaped tin objects stand in rows behind piles of hammers and modelling frames. After so many weeks and months of Saturday noons the boy begins to lose touch with his former friends and companions, who go their separate ways.

A primal scene? The boy is eleven, starting seventh grade. His father explains that it is time to learn the value of work. He has arranged a job for his son with a friend whose name is Cutting and who owns a sheet metal shop. Every Saturday the boy rides his bicycle across town to Cutting’s Sheet Metal. The employees are done for the week at noon on Saturday. He has to arrive by noon so the boss can lock up, leaving the boy inside (he is too young to be trusted with a key). The job is to clean the shop — sweep the floor, gather up the tools and align them neatly in their designated places on the work benches, collect the remnants and clippings of the metal sheets scattered everywhere. It takes most of the afternoon to finish the chores. The shop is a cavernous open warehouse, with rows of heavy tables, the walls lined with shelves stacked to the distant ceiling with equipment, tools, metals. It is quiet, the stillness of dust motes swirling in the beams of sunlight filtered through the few windows high up near the roof, carving vectors through deep shadow. The sunlight catches the edges of a museum of blades, a taxonomy of every snipping snap slice chop saw hack rend rip cleave nip or severing machine. Half-shaped tin objects stand in rows behind piles of hammers and modelling frames. After so many weeks and months of Saturday noons the boy begins to lose touch with his former friends and companions, who go their separate ways. What happens then? The light and shadow of the industrial building open all at once onto a void, a black hole and white wall of divided worlds in this little infinite town: the official world of adults (parents, teachers, coaches, ministers, scout masters) that until then had constituted reality, and the unofficial world of his peers, whose existence he had only just discovered. Two completely different systems of virtue and vice, success and failure, winning and losing, visibility and invisibility, were enforced in these realms: systems Not only different, but opposite and in conflict. What earned admiration and respect in one was inversely judged in the other. He could not have articulated the revelation so abstractly then. The unexpected aspect of this scene is the sense of abandonment, solitary isolation, that overcomes the child, a spilling out or abjection, an absolute exhaling of substance, followed soon after by the inhaled relief of knowing that it doesn’t matter, since everyone and everything dies everywhere the same death.

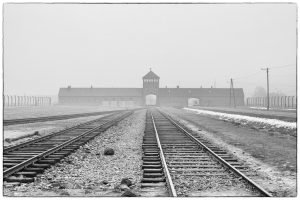

What happens then? The light and shadow of the industrial building open all at once onto a void, a black hole and white wall of divided worlds in this little infinite town: the official world of adults (parents, teachers, coaches, ministers, scout masters) that until then had constituted reality, and the unofficial world of his peers, whose existence he had only just discovered. Two completely different systems of virtue and vice, success and failure, winning and losing, visibility and invisibility, were enforced in these realms: systems Not only different, but opposite and in conflict. What earned admiration and respect in one was inversely judged in the other. He could not have articulated the revelation so abstractly then. The unexpected aspect of this scene is the sense of abandonment, solitary isolation, that overcomes the child, a spilling out or abjection, an absolute exhaling of substance, followed soon after by the inhaled relief of knowing that it doesn’t matter, since everyone and everything dies everywhere the same death. The method is counterintuitive, in that egents turn away from the historical catastrophe, in order to access their peculiar power. The instructions derived from the text are to compose a figure by juxtaposing a childhood memory with a collective event (a disaster). Blanchot calls this memory a primal scene. It represents an early if not first experience of self-awareness of the human condition – an existential intuition. The corresponding event for Blanchot is the Holocaust.

The method is counterintuitive, in that egents turn away from the historical catastrophe, in order to access their peculiar power. The instructions derived from the text are to compose a figure by juxtaposing a childhood memory with a collective event (a disaster). Blanchot calls this memory a primal scene. It represents an early if not first experience of self-awareness of the human condition – an existential intuition. The corresponding event for Blanchot is the Holocaust. (A primal scene?) You who live later, close to a heart that beats no more, suppose, suppose this: the child – is he seven years old, or eight perhaps? – standing by the window, drawing the curtain and, through the pane, looking. What he sees: the garden, the wintry trees, the wall of a house. Though he sees, no doubt in a child’s way, his play space, he grows weary and slowly looks up toward the ordinary sky, with clouds, grey light – pallid daylight without depth.

(A primal scene?) You who live later, close to a heart that beats no more, suppose, suppose this: the child – is he seven years old, or eight perhaps? – standing by the window, drawing the curtain and, through the pane, looking. What he sees: the garden, the wintry trees, the wall of a house. Though he sees, no doubt in a child’s way, his play space, he grows weary and slowly looks up toward the ordinary sky, with clouds, grey light – pallid daylight without depth.