WIDE IMAGE 5

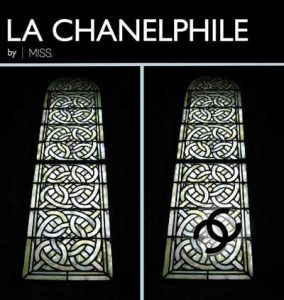

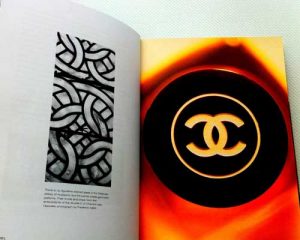

5) Design Relay: Coco Chanel. Design is electrate écriture (konsult is designed). Design in general and in its various specialized applications is a resource for composing wide image since there is a legible continuity relating the memory event with the gesture defining the designer’s style. Coco Chanel is a case in point. In her account of the life and career of the designer Coco Chanel, (Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life), Justine Picardie explains the origins of Chanel’s Logo as alluding to the arabesque patterns of the stained glass windows in the convent that took care of destitute children, the Cistercian abbey at Aubazine, where Chanel lived from the time she was 12 years old, until age 18. This match between a detail from a childhood memory and the adult career is a signal that an image of wide scope is at work. It is worth noting in this context the archetype that is latent within and no doubt deliberately invoked by Chanel’s design: the sacred geometric figure known as

5) Design Relay: Coco Chanel. Design is electrate écriture (konsult is designed). Design in general and in its various specialized applications is a resource for composing wide image since there is a legible continuity relating the memory event with the gesture defining the designer’s style. Coco Chanel is a case in point. In her account of the life and career of the designer Coco Chanel, (Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life), Justine Picardie explains the origins of Chanel’s Logo as alluding to the arabesque patterns of the stained glass windows in the convent that took care of destitute children, the Cistercian abbey at Aubazine, where Chanel lived from the time she was 12 years old, until age 18. This match between a detail from a childhood memory and the adult career is a signal that an image of wide scope is at work. It is worth noting in this context the archetype that is latent within and no doubt deliberately invoked by Chanel’s design: the sacred geometric figure known as  the Vesica Piscis

the Vesica Piscis

Chanel created the Little Black Dress (so accepted in popular culture that it is known by its acronym LBD). Perhaps the most famous LBD was worn by Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, but it has been present in numerous other films. The correspondence between the nun habits of memory and the secular fashion of the liberated woman creates a hybrid in popular erotic fantasy.

4) Childhood Memory: Renzo Piano.Hal Foster was in Gainesville to give a lecture for the Architecture School. The theme was Neomodernism, focusing on Norman Foster and Renzo Piano. I had not heard the story before about the role that childhood memories played in Piano’s aesthetic. It is another example of an image of wide scope, the formatting of an imagination in specific childhood experiences. There are two memories that reinforce one another in Piano’s case: one of watching sailing ships in the port city of Genoa, his hometown; the other of laundry blowing in the wind on the roofs of the city.

4) Childhood Memory: Renzo Piano.Hal Foster was in Gainesville to give a lecture for the Architecture School. The theme was Neomodernism, focusing on Norman Foster and Renzo Piano. I had not heard the story before about the role that childhood memories played in Piano’s aesthetic. It is another example of an image of wide scope, the formatting of an imagination in specific childhood experiences. There are two memories that reinforce one another in Piano’s case: one of watching sailing ships in the port city of Genoa, his hometown; the other of laundry blowing in the wind on the roofs of the city. The 95-story skyscraper Piano designed for the Shard Quarter in London expresses the sail as its Idea or parti. Architects are good relays for this translation of wide image into hypothesis since their

The 95-story skyscraper Piano designed for the Shard Quarter in London expresses the sail as its Idea or parti. Architects are good relays for this translation of wide image into hypothesis since their

3) Memory: Frank Gehry.In their book about the architect, Frank Gehry (best known for his design of the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao, Spain), Jan Greenberg and Sandra Jordan (Frank O. Gehry: Outside In) describe the connection between Gehry’s childhood memories and his career in a way that resonates with the principle of the wide image.

3) Memory: Frank Gehry.In their book about the architect, Frank Gehry (best known for his design of the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao, Spain), Jan Greenberg and Sandra Jordan (Frank O. Gehry: Outside In) describe the connection between Gehry’s childhood memories and his career in a way that resonates with the principle of the wide image.

2) Childhood Memory: Einstein’s Themata.

2) Childhood Memory: Einstein’s Themata. –Exercise. There is no need to understand all the features of mystory, wide image, heuretics, popcycle, before beginning the discovery and design project. We may begin with a memory exercise, to notice what scene remains in memory. The instructions are just to reflect for a few minutes on one’s early childhood, to observe what may appear, to take note, to save the scene for development later on. Record the memory in anecdote form (300-word flash fiction) illustrated with found images. The exercise may also be applied analytically to biographies of interest. We will inventory a number of cases of such early memories.

–Exercise. There is no need to understand all the features of mystory, wide image, heuretics, popcycle, before beginning the discovery and design project. We may begin with a memory exercise, to notice what scene remains in memory. The instructions are just to reflect for a few minutes on one’s early childhood, to observe what may appear, to take note, to save the scene for development later on. Record the memory in anecdote form (300-word flash fiction) illustrated with found images. The exercise may also be applied analytically to biographies of interest. We will inventory a number of cases of such early memories.