Terms: Popcycle 2

| POPCYCLE (EXPANDED FIELD) |

Meanwhile, some reflection on the popcycle diagram, by way of a question, to ask about your experience with the generative power of diagrams. The mise-en-abyme layout is not formally motivated, nor is there any one structure required to register the components. Derrida’s reference to heraldry was one inspiration, having in mind his ambivalent explorations of abyssal figures, extending not only to modernist tropes, but to the structure of Plato’s Timaeus and the operations of chora. I referred to it in terms of the fibonacigeometry of the whirling square (in Internet Invention), to call attention to its dynamics, as vortex (Pound). The figure will be unpacked further, since I have used it to think together every four (+1) series and set that presents itself, in the spirit of the four-color theorem: four causes (ancient and modern), suits of cards, divination systems, four (or five) tastes, the cardinal tropes, cardinal and ordinal directions, and more.

When it comes to the image of wide scope (four or five fundamental images structuring imagination, and central to the history of invention), the prototype is Einstein’s compass (received from his father as a gift at age four or five): the wide image is a compass for the existential positioning system of learning, to orient egents tracking the vector of invention.

When it comes to the image of wide scope (four or five fundamental images structuring imagination, and central to the history of invention), the prototype is Einstein’s compass (received from his father as a gift at age four or five): the wide image is a compass for the existential positioning system of learning, to orient egents tracking the vector of invention.

Coming across the work of Stephen Willats, I recognized the diagram in Perceptions of a Married Couple (1975), which prompted the thought that I should do a systematic search to trace the diagram conductively. “In ‘Perceptions of a Married Couple’ , the main focus is in the relationship between the form of the inter-personal network that underlies perception of self and others and the resulting generation of social attitudes. It was Willats’ first work where people were photographed within the coded world they themselves had actually constructed.”

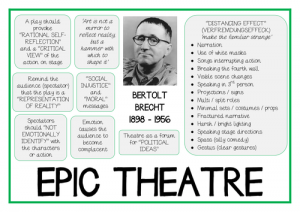

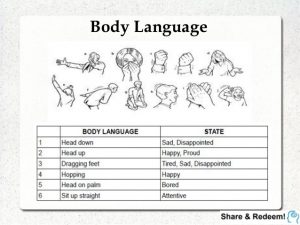

“Gest” is not supposed to mean gesticulation: it is not a matter of explana-tory or emphatic movements of the hands, but of overall attitudes. A language is gestic when it is grounded in a gest and conveys particular attitudes adopted by the speaker towards other men. The sentence “pluck the eye that offends thee out” is less effective from the gestic point of view than “if thine eve offend thee, pluck it out.” The latter starts by pre-senting the eye, and the first clause has the definite gest of making an assumption; the main clause then comes as a surprise, a piece of advice, and a relief.

“Gest” is not supposed to mean gesticulation: it is not a matter of explana-tory or emphatic movements of the hands, but of overall attitudes. A language is gestic when it is grounded in a gest and conveys particular attitudes adopted by the speaker towards other men. The sentence “pluck the eye that offends thee out” is less effective from the gestic point of view than “if thine eve offend thee, pluck it out.” The latter starts by pre-senting the eye, and the first clause has the definite gest of making an assumption; the main clause then comes as a surprise, a piece of advice, and a relief. Suppose that the musician composing a cantata on Lenin’s death has to reproduce his own attitude to the class struggle. As far as the gest goes, there are a number of different ways in which the report of Lenin’s death can be set. A certain dignity of presentation means little, since where death is involved this could also be held to be fitting in the case of an enemy. Anger at ‘the blind workings of providence’ cutting short the lives of the best members of the community would not be a communist gest; nor would a wise resignation to “life’s irony”; for the gest of communists mourning a communist is a very special one. The musician’s attitude to his text, the spokesman’s to his report, shows the extent of his political, and so of his human maturity. A man’s stature is shown by what he mourns and in what way he mourns it. To raise mourning to a high plane, to make it into an element of social progress: that is an artistic task.

Suppose that the musician composing a cantata on Lenin’s death has to reproduce his own attitude to the class struggle. As far as the gest goes, there are a number of different ways in which the report of Lenin’s death can be set. A certain dignity of presentation means little, since where death is involved this could also be held to be fitting in the case of an enemy. Anger at ‘the blind workings of providence’ cutting short the lives of the best members of the community would not be a communist gest; nor would a wise resignation to “life’s irony”; for the gest of communists mourning a communist is a very special one. The musician’s attitude to his text, the spokesman’s to his report, shows the extent of his political, and so of his human maturity. A man’s stature is shown by what he mourns and in what way he mourns it. To raise mourning to a high plane, to make it into an element of social progress: that is an artistic task. The creative individual pursues (or is pursued by) a number of dominant metaphors. These figures are images of wide scope, rich, and susceptible to considerable exploration, exposing the investigator to aspects of phenomena that might otherwise remain invisible to him. Often the key to the individual’s most important innovations inhere in these images. In Darwin’s case, the most fecund metaphor was the branching tree of evolution, on which he could trace the rise and fate of various species. Gruber’s students have uncovered other such metaphors of wide scope. William James had a penchant for viewing mental processes as a stream or river, rather than in terms of the associationist images of a train or a chain. Any consideration of John Locke should focus on his falconer, whose release of a bird symbolized the quest for human knowledge. Finally, in conveying his own emerging view of the creative process, Gruber finds himiself attracted to the Mosaic image of the bush that is always burning but never consumed. (Howard Gardner, Art, Mind, and Brain: A Cognitive Approach to Creativity).

The creative individual pursues (or is pursued by) a number of dominant metaphors. These figures are images of wide scope, rich, and susceptible to considerable exploration, exposing the investigator to aspects of phenomena that might otherwise remain invisible to him. Often the key to the individual’s most important innovations inhere in these images. In Darwin’s case, the most fecund metaphor was the branching tree of evolution, on which he could trace the rise and fate of various species. Gruber’s students have uncovered other such metaphors of wide scope. William James had a penchant for viewing mental processes as a stream or river, rather than in terms of the associationist images of a train or a chain. Any consideration of John Locke should focus on his falconer, whose release of a bird symbolized the quest for human knowledge. Finally, in conveying his own emerging view of the creative process, Gruber finds himiself attracted to the Mosaic image of the bush that is always burning but never consumed. (Howard Gardner, Art, Mind, and Brain: A Cognitive Approach to Creativity). –Steven Spielberg. Sarah Boxer asked Steven Spielberg to recall his earliest visual experience. He found one from the age of 3.

–Steven Spielberg. Sarah Boxer asked Steven Spielberg to recall his earliest visual experience. He found one from the age of 3. 6) Memory Exercise: Kandinsky. As illustrated by the careers of productive people, at some point an interviewer will ask about an early memory from childhood. Mystory may adopt such interviews–the kind of things people want to know about the sources and motivations of creativity–as a guide to identify similar resources in one’s own biography to bring into the wide image matrix. Exercise: read an interview with a creative person of interest, inventory the questions asked, and answer them in your own case.

6) Memory Exercise: Kandinsky. As illustrated by the careers of productive people, at some point an interviewer will ask about an early memory from childhood. Mystory may adopt such interviews–the kind of things people want to know about the sources and motivations of creativity–as a guide to identify similar resources in one’s own biography to bring into the wide image matrix. Exercise: read an interview with a creative person of interest, inventory the questions asked, and answer them in your own case.

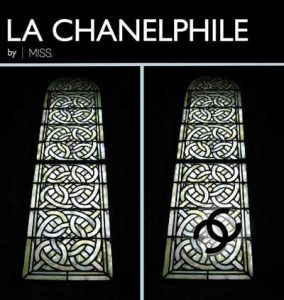

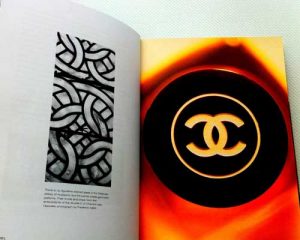

5) Design Relay: Coco Chanel. Design is electrate écriture (konsult is designed). Design in general and in its various specialized applications is a resource for composing wide image since there is a legible continuity relating the memory event with the gesture defining the designer’s style. Coco Chanel is a case in point. In her account of the life and career of the designer Coco Chanel, (Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life), Justine Picardie explains the origins of Chanel’s Logo as alluding to the arabesque patterns of the stained glass windows in the convent that took care of destitute children, the Cistercian abbey at Aubazine, where Chanel lived from the time she was 12 years old, until age 18. This match between a detail from a childhood memory and the adult career is a signal that an image of wide scope is at work. It is worth noting in this context the archetype that is latent within and no doubt deliberately invoked by Chanel’s design: the sacred geometric figure known as

5) Design Relay: Coco Chanel. Design is electrate écriture (konsult is designed). Design in general and in its various specialized applications is a resource for composing wide image since there is a legible continuity relating the memory event with the gesture defining the designer’s style. Coco Chanel is a case in point. In her account of the life and career of the designer Coco Chanel, (Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life), Justine Picardie explains the origins of Chanel’s Logo as alluding to the arabesque patterns of the stained glass windows in the convent that took care of destitute children, the Cistercian abbey at Aubazine, where Chanel lived from the time she was 12 years old, until age 18. This match between a detail from a childhood memory and the adult career is a signal that an image of wide scope is at work. It is worth noting in this context the archetype that is latent within and no doubt deliberately invoked by Chanel’s design: the sacred geometric figure known as  the

the

4) Childhood Memory: Renzo Piano.Hal Foster was in Gainesville to give a lecture for the Architecture School. The theme was Neomodernism, focusing on Norman Foster and Renzo Piano. I had not heard the story before about the role that childhood memories played in Piano’s aesthetic. It is another example of an image of wide scope, the formatting of an imagination in specific childhood experiences. There are two memories that reinforce one another in Piano’s case: one of watching sailing ships in the port city of Genoa, his hometown; the other of laundry blowing in the wind on the roofs of the city.

4) Childhood Memory: Renzo Piano.Hal Foster was in Gainesville to give a lecture for the Architecture School. The theme was Neomodernism, focusing on Norman Foster and Renzo Piano. I had not heard the story before about the role that childhood memories played in Piano’s aesthetic. It is another example of an image of wide scope, the formatting of an imagination in specific childhood experiences. There are two memories that reinforce one another in Piano’s case: one of watching sailing ships in the port city of Genoa, his hometown; the other of laundry blowing in the wind on the roofs of the city. The 95-story skyscraper Piano designed for the Shard Quarter in London expresses the sail as its Idea or parti. Architects are good relays for this translation of wide image into hypothesis since their

The 95-story skyscraper Piano designed for the Shard Quarter in London expresses the sail as its Idea or parti. Architects are good relays for this translation of wide image into hypothesis since their

3) Memory: Frank Gehry.In their book about the architect, Frank Gehry (best known for his design of the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao, Spain), Jan Greenberg and Sandra Jordan (Frank O. Gehry: Outside In) describe the connection between Gehry’s childhood memories and his career in a way that resonates with the principle of the wide image.

3) Memory: Frank Gehry.In their book about the architect, Frank Gehry (best known for his design of the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao, Spain), Jan Greenberg and Sandra Jordan (Frank O. Gehry: Outside In) describe the connection between Gehry’s childhood memories and his career in a way that resonates with the principle of the wide image.

2) Childhood Memory: Einstein’s Themata.

2) Childhood Memory: Einstein’s Themata. –Exercise. There is no need to understand all the features of mystory, wide image, heuretics, popcycle, before beginning the discovery and design project. We may begin with a memory exercise, to notice what scene remains in memory. The instructions are just to reflect for a few minutes on one’s early childhood, to observe what may appear, to take note, to save the scene for development later on. Record the memory in anecdote form (300-word flash fiction) illustrated with found images. The exercise may also be applied analytically to biographies of interest. We will inventory a number of cases of such early memories.

–Exercise. There is no need to understand all the features of mystory, wide image, heuretics, popcycle, before beginning the discovery and design project. We may begin with a memory exercise, to notice what scene remains in memory. The instructions are just to reflect for a few minutes on one’s early childhood, to observe what may appear, to take note, to save the scene for development later on. Record the memory in anecdote form (300-word flash fiction) illustrated with found images. The exercise may also be applied analytically to biographies of interest. We will inventory a number of cases of such early memories.